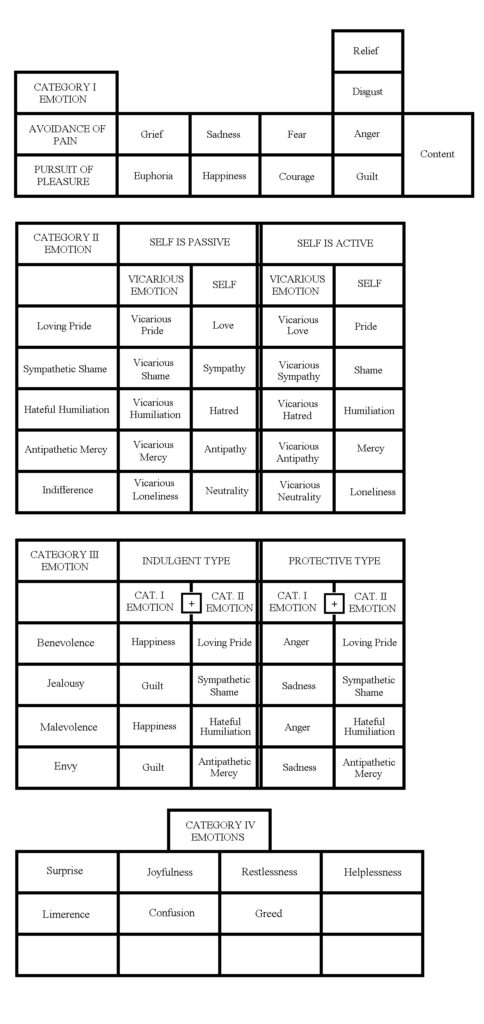

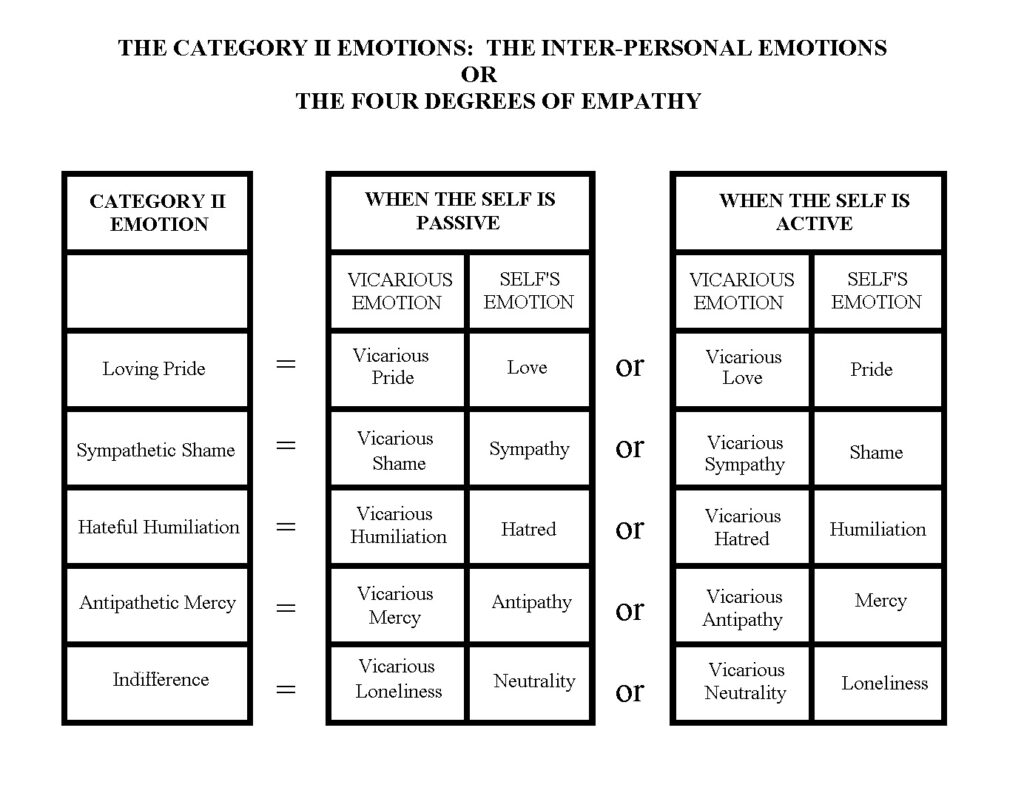

Category II Emotions: the Inter-personal Emotions or the Four Degrees of Empathy

Category II Emotions: the Inter-personal Emotions or the Four Degrees of Empathy

This article gives an overview of Category II Emotions (the Inter-personal Emotions or Four Degrees of Empathy) in Affect Engineering. It is the eighth article in a series of twelve designed for the layperson that explains the basics of Affect Engineering as a theory of emotions. Each article will begin with a list of questions that it will aim to address. The sections that follow will be in two parts each. The first part will be a short statement that answers each question as succinctly as possible. The second part will either be an explanation that goes into more detail where needed or explain some of the implications of the short answer.

*Note, this article contains some movie spoilers, albeit for older films.*

QUESTIONS

- What are the Category II Emotions and what distinguishes them from Category I and Category III Emotions?

- Why are there only four degrees of empathy in Affect Engineering if there are five pairs of Category II Emotions?

- Why does Affect Engineering bother to distinguish emotions that are experienced vicariously depending on whether or not one party has the ability to influence the outcome of another party’s situation?

- For what reasons might an individual intentionally alter their identification level with a target?

1) What are the Category II Emotions and what distinguishes them from Category I and Category III Emotions?

SHORT ANSWER

Category II Emotions in Affect Engineering concern instances where one party vicariously experiences the situation of another party but has no ability to influence the outcome (i.e., they are completely passive). Category II Emotions always involve empathy, and the presence of empathy distinguishes them from Category I Emotions. Additionally, Category II Emotions always have a party that is passively empathizing with the observed party, and the passivity of one party distinguishes them from Category III Emotions where the empathizing party can actively influence the outcome for the other’s situation.

IN DEPTH EXPLANATION

Category II Emotions are organized into two separate, but related, groups. Love, Sympathy, Hate, Antipathy, and Neutrality are felt by the passive party that is observing the active party. The passive party imagines themself as the target and desires to vicariously experience the target’s success (for Love and Sympathy), or their failure (for Hate and Antipathy), or neither (for Neutrality).

The other group, consisting of Pride, Shame, Humiliation, Mercy, and Loneliness, are construed in Affect Engineering as emotional responses arising in the target from awareness that their circumstances and the outcome are being empathized with in some manner by an observing party (for Pride, Shame, Humiliation, and Mercy), or not empathized with at all in the case of Loneliness.

Altogether, there are five pairs. Each pair may have one of two constructions depending on which party is passively observing and which party is actively attempting to influence the outcome for a scenario and a relevant purpose. For the following examples, the self will be assumed to be passively observing and empathizing with a targeted party that is actively attempting to achieve a purpose.

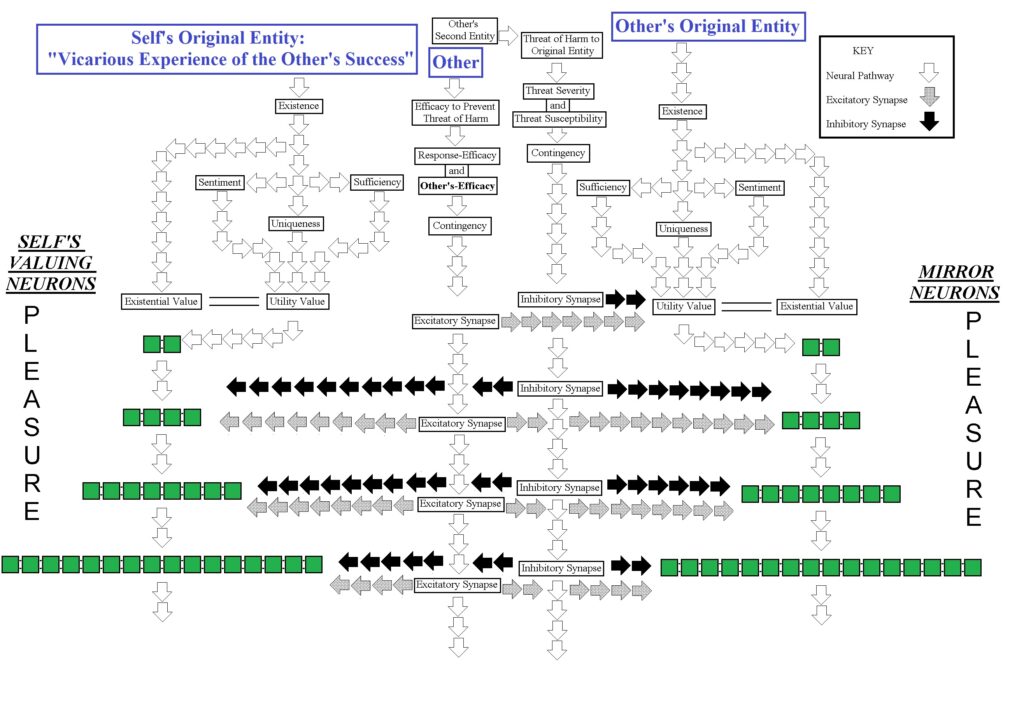

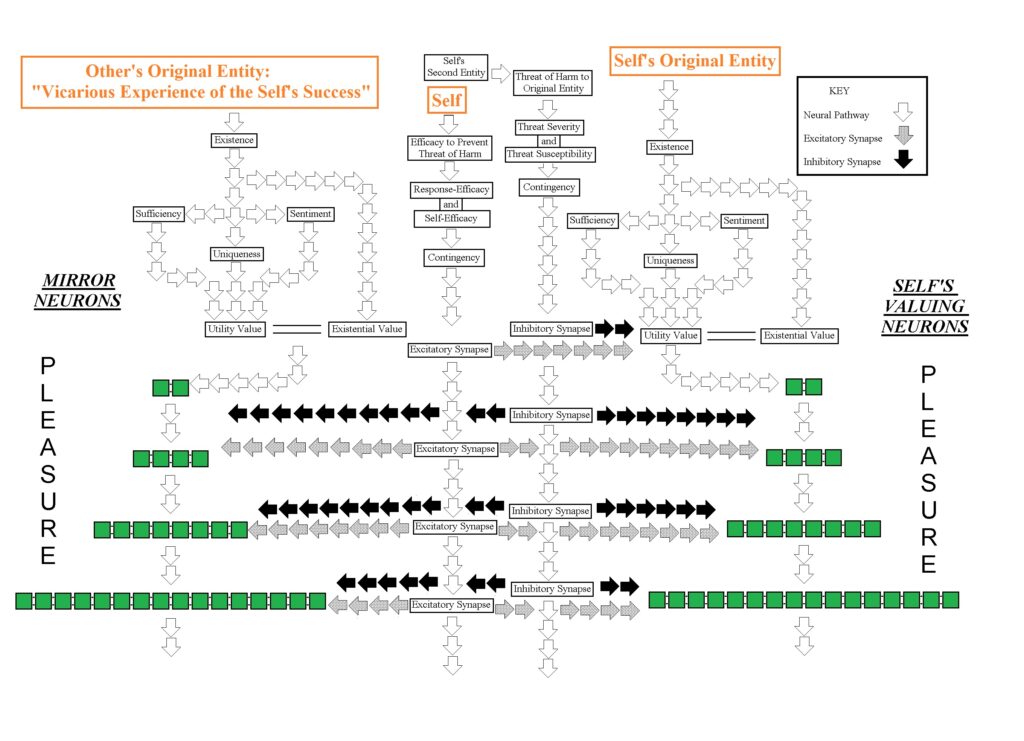

For the case of Loving Pride in Affect Engineering, the self would desire for the targeted party to succeed and subsequently, to vicariously experience their success. If the other party succeeds, then this would be classified as an instance of love in Affect Engineering. Love, in this context, is construed as a sense of satisfaction at having acknowledged and vicariously experienced another’s success and good fortune; it is not love in the romantic sense, which often entails additional objectives. Pride, a sense of accomplishment arising when a goal has been achieved and also recognized and approved by others, would be modeled to occur in conjunction with this from the targeted party; pride would arise from the awareness by the targeted party that the self desires for them to succeed and they are being admired for it because they did succeed. Pride, in this context, is understood as an emotional response in the loved party.

Moreover, because the self is not the loved party (the self is the one doing the loving) and they are only passively observing, they would not be modeled to feel pride themselves directly. The targeted party would feel pride if they are aware that the self or any other empathizing party wants them to succeed and they do succeed. The self, at the very least, knows that they want the targeted party to succeed, and so the self would be modeled to feel vicarious pride along with love in Affect Engineering.

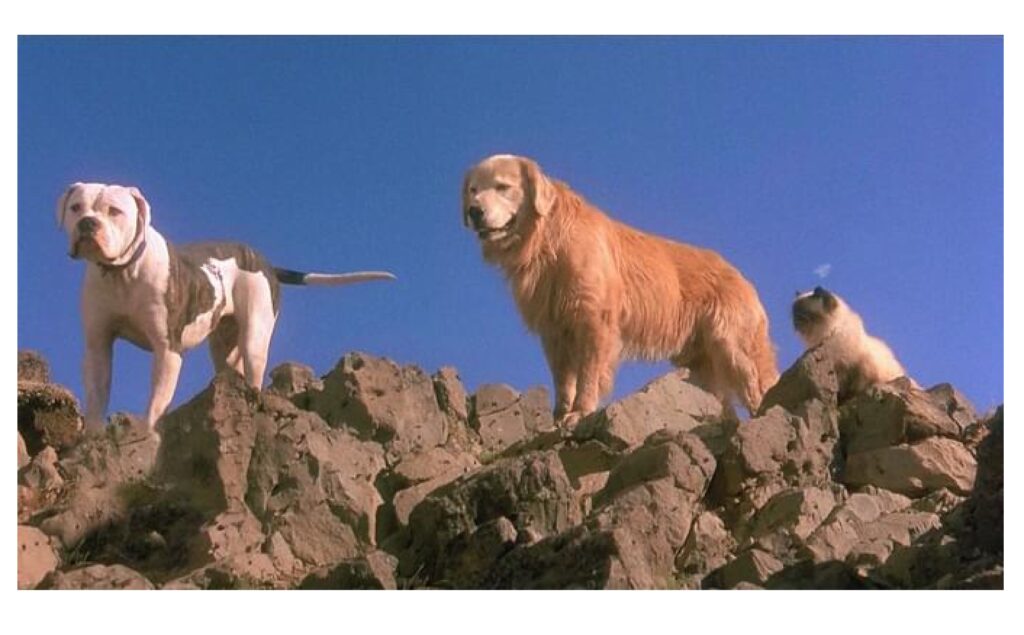

- In the Love and Vicarious Pride variant of Loving Pride, an observer, (e.g., the self) desires for the targeted party to achieve their goal, and they succeed. For the targeted party, the goal might be something as simple as a desire to safely return home, as was the case for the crew of astronauts in the movie Apollo 13 (1995), (link to Roger Ebert’s review of Apollo 13 with some background for those unfamiliar with the story). Another example would be the pets Shadow, Sassy, and Chance in the Disney movie Homeward Bound: The Incredible Journey (1993) (link to the Homeward Bound Disney movie trailer). For individuals watching and wanting the targeted parties to succeed, these would be modeled as instances of Love in Affect Engineering. The self wants the target party to succeed and the targeted party does succeed. Both movies have happy endings, given that they are mentioned in this group of Category II Emotions, and take a fairly direct approach in the sense that viewers are expected to want these characters to succeed.

- The targeted parties, if they were aware that the self were observing them, would feel pride at the acknowledgement that the self wanted them to succeed, in this case by safely returning home. Because these are movies filmed beforehand, this is not technically possible, but it can be simulated with other characters and family members in the story that want them to succeed. The self can then more easily imagine being in the position of the characters feeling loved for safely returning home. The self would feel vicarious pride, imagining themself as the targeted party feeling pride for safely returning home, if the supporting characters are likable enough that audience members can also identify with them.

- The hero, if they were aware that they were being empathized, would be modeled to feel Vicarious Love, imagining themself as the self or another spectator wanting them to succeed. If a story is well written, then whoever is waiting for the hero to return home would ideally be someone that an audience member or viewer can easily identify with in order to be more effective (e.g., family members of the astronauts Jim Lovell, Fred Haise, and Jack Swigert, or the three children Peter, Jamie, and Hope who the pets identify as their owners in Homeward Bound).

An example of Loving Pride (e.g., Love and Vicarious Pride variant) felt by the audience. Apollo 13 (1995) with Jim Lovell (portrayed by Tom Hanks), Fred Haise (portrayed by Bill Paxton) and Jack Swigert (portrayed by Kevin Bacon).

An example of Loving Pride (e.g., Love and Vicarious Pride variant) felt by the audience. Chance, Shadow, and Sassy from the movie Homeward Bound: The Incredible Journey (1993).

For each party (i.e., the self and the other), one of the two emotions would be felt as a vicarious one while the other emotion would be felt for the individual themself. If the self were instead the active party in the story, then the emotions felt would be flipped with the self feeling Pride and Vicarious Love and the other party feeling Love and Vicarious Pride. As each was a movie filmed beforehand, the closest scenario that this could be the case would be if the real life astronauts that the Apollo 13 movie was based on watched the movie version of their ordeal with their characters being portrayed by famous actors (e.g., Tom Hanks, Bill Paxton, Kevin Bacon). Not surprisingly, after watching the film, actual Apollo 13 captain Jim Lovell said in a statement in the Independent, “More than 50 years after the mission, the film put me right back in the captain’s seat.”

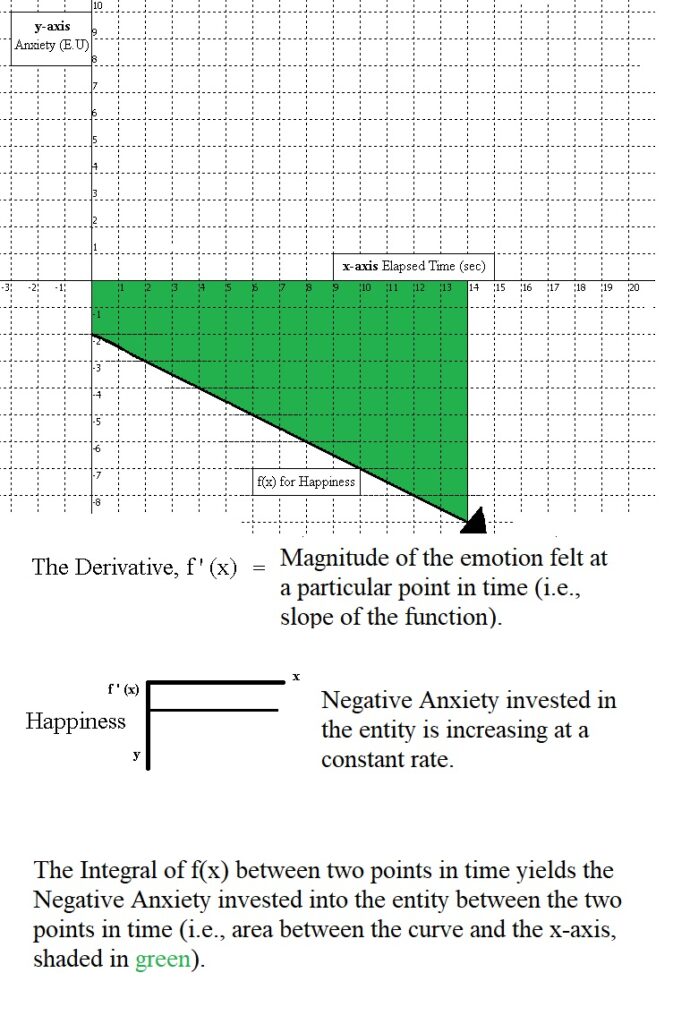

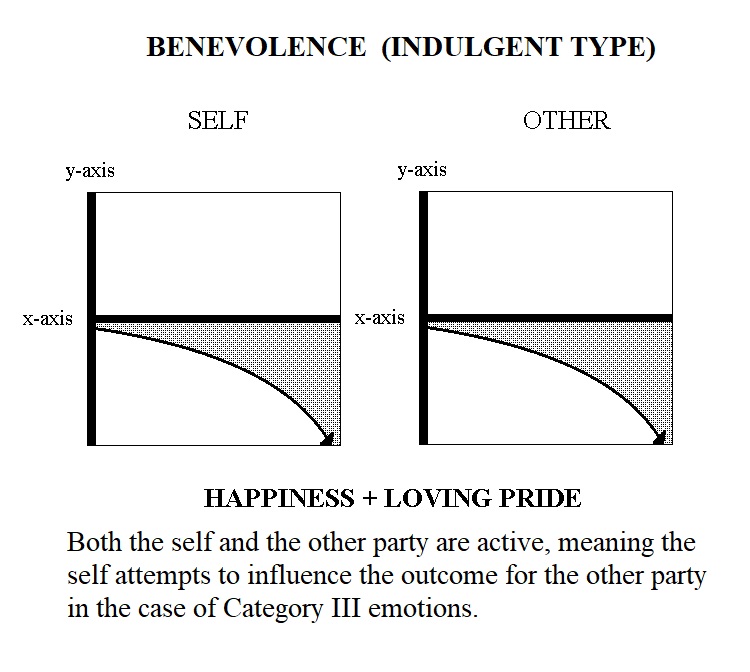

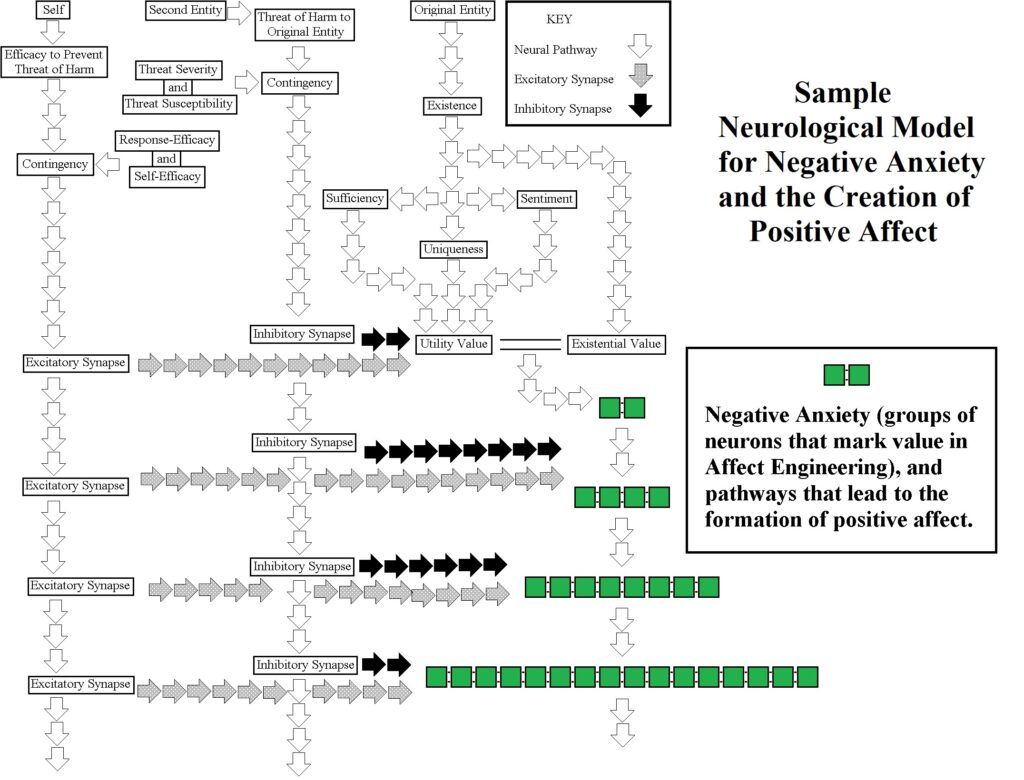

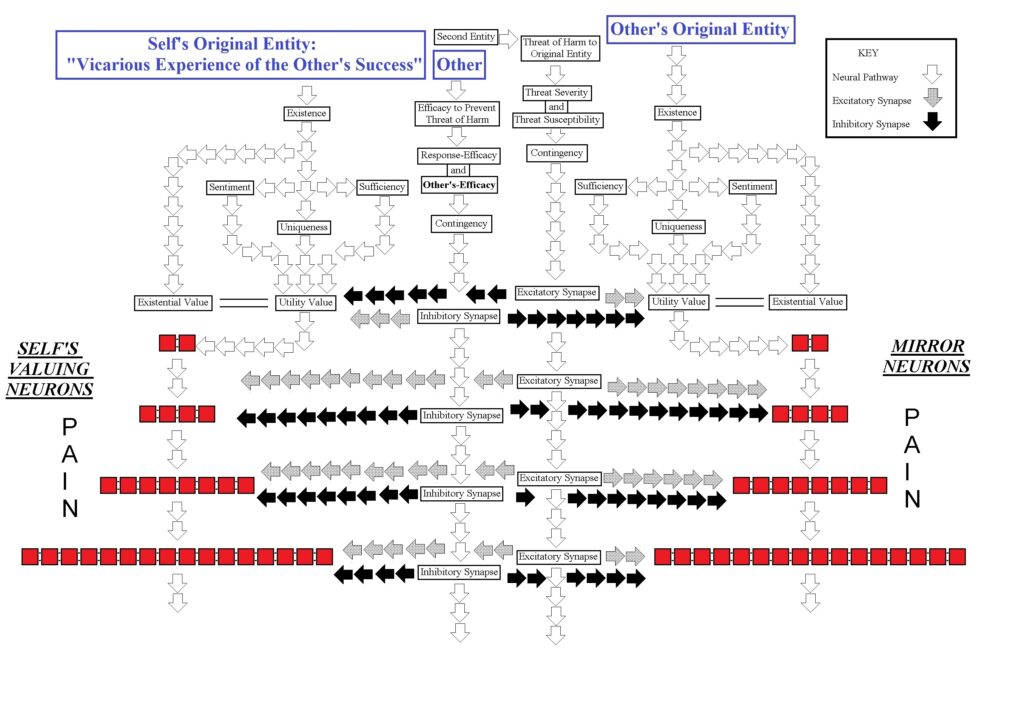

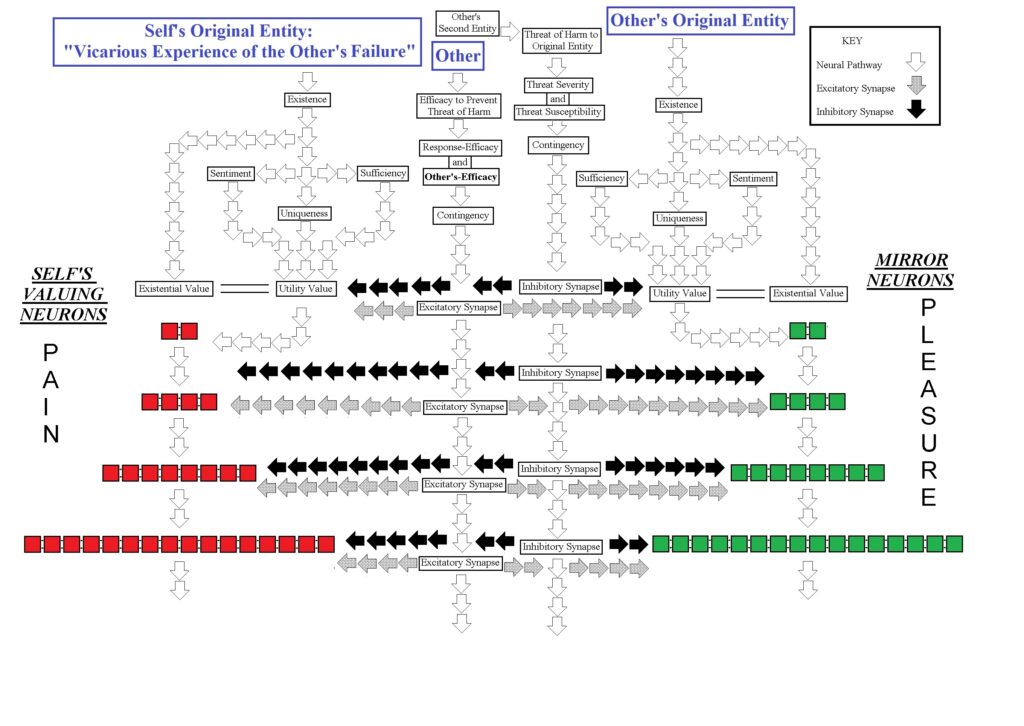

Image 3a (below) Sample neural model for Loving Pride where the self is the passive party and feels Love and Vicarious Pride.

Image 3b (below) Sample neural model for Loving Pride where the self is the active party and feels Pride and Vicarious Love.

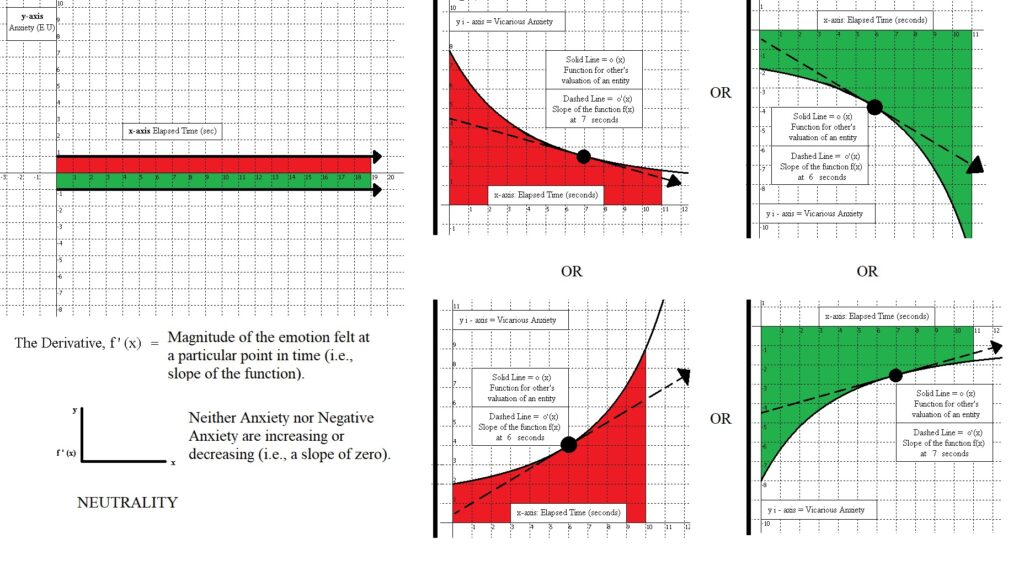

The passive party vs. active party dynamic applies to all of the other Category II Emotions in Affect Engineering as well. The passive party will either feel Love and Vicarious Pride, Sympathy and Vicarious Shame, Hate and Vicarious Humiliation, Antipathy and Vicarious Mercy, or Neutrality and Vicarious Loneliness. The active party will either feel Pride and Vicarious Love, Shame and Vicarious Sympathy, Humiliation and Vicarious Hate, Mercy and Vicarious Antipathy, or Loneliness and Vicarious Neutrality.

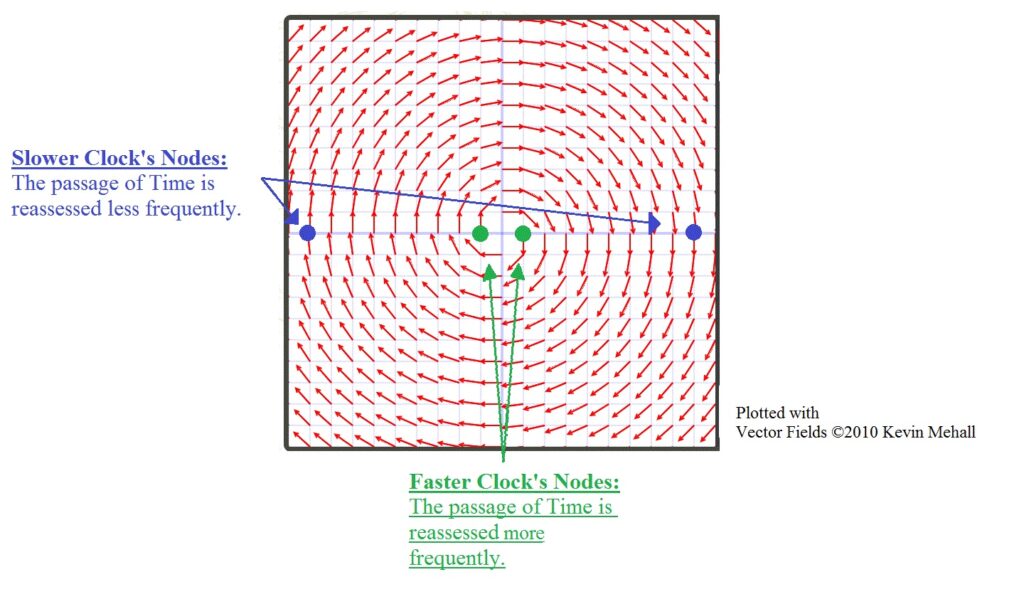

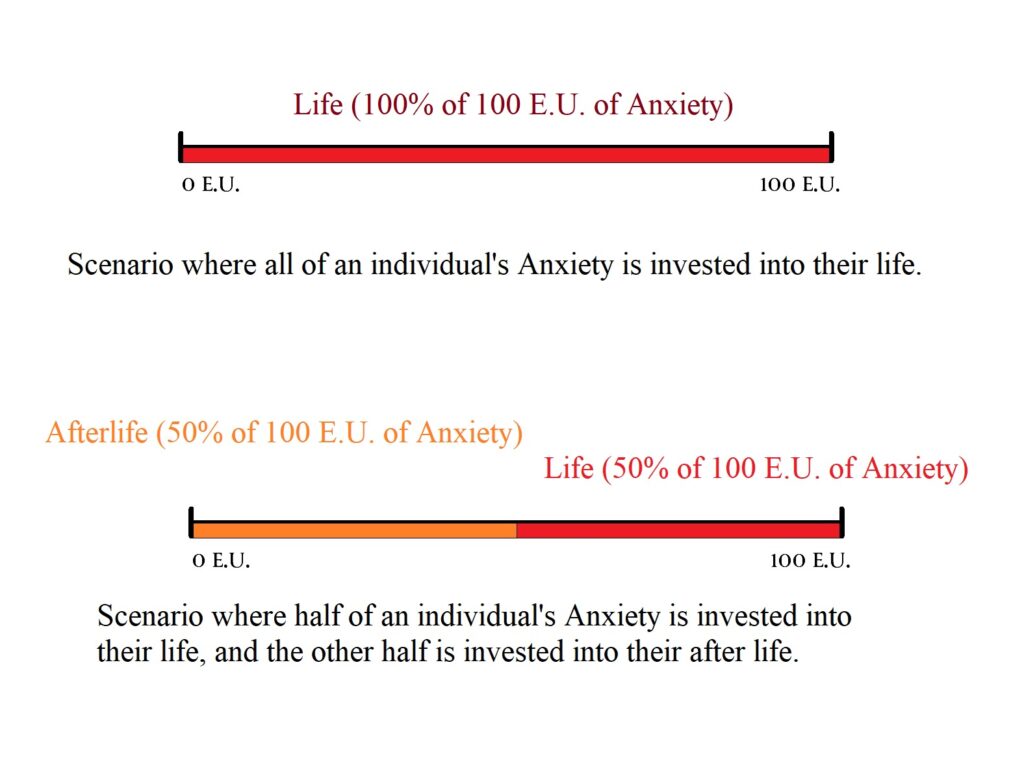

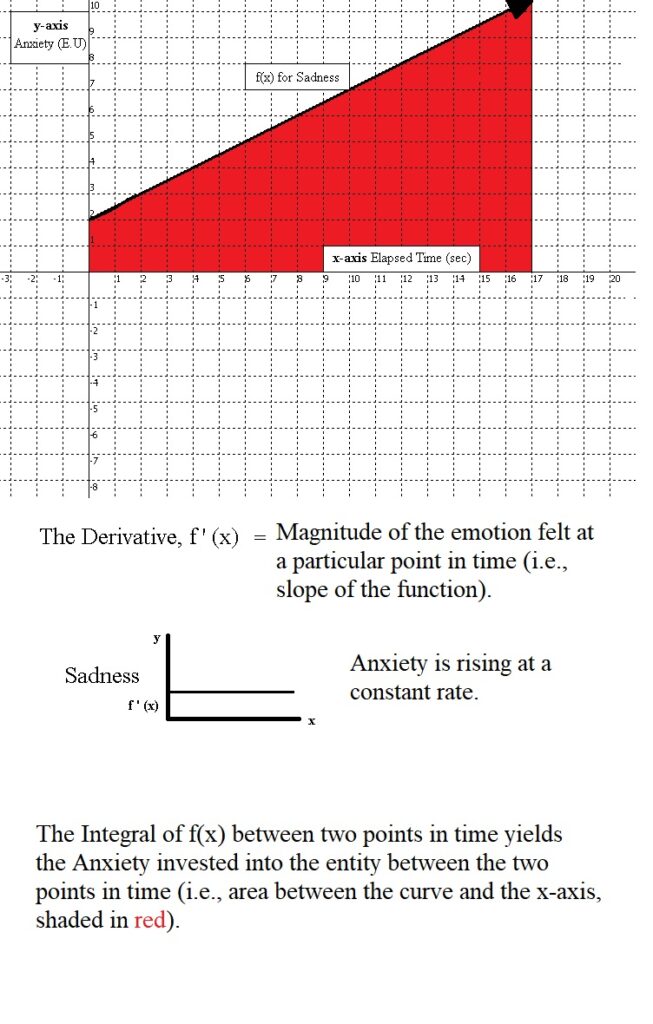

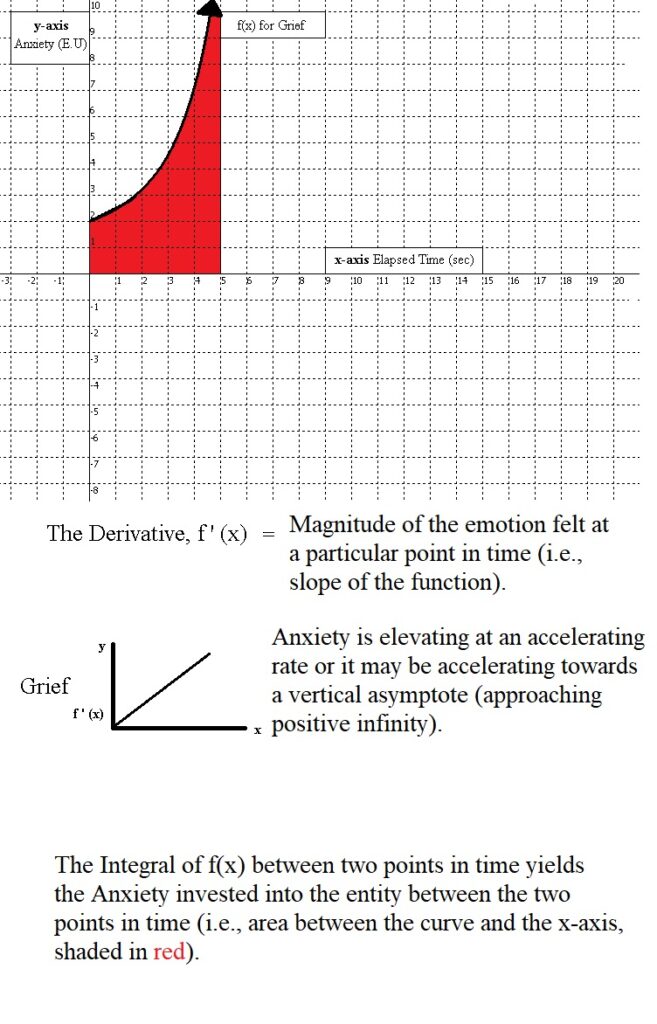

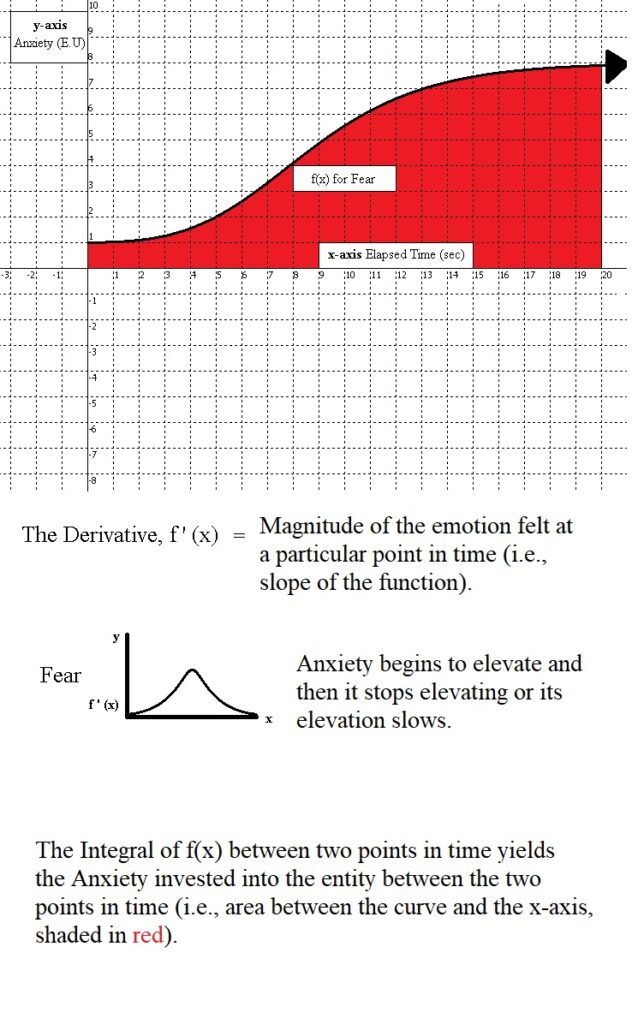

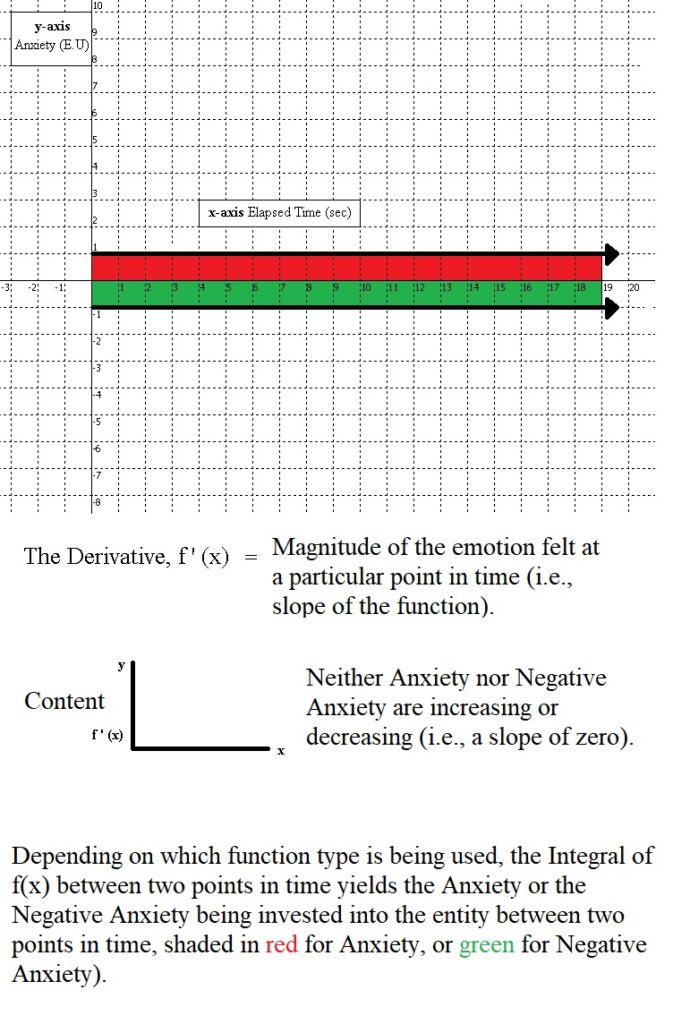

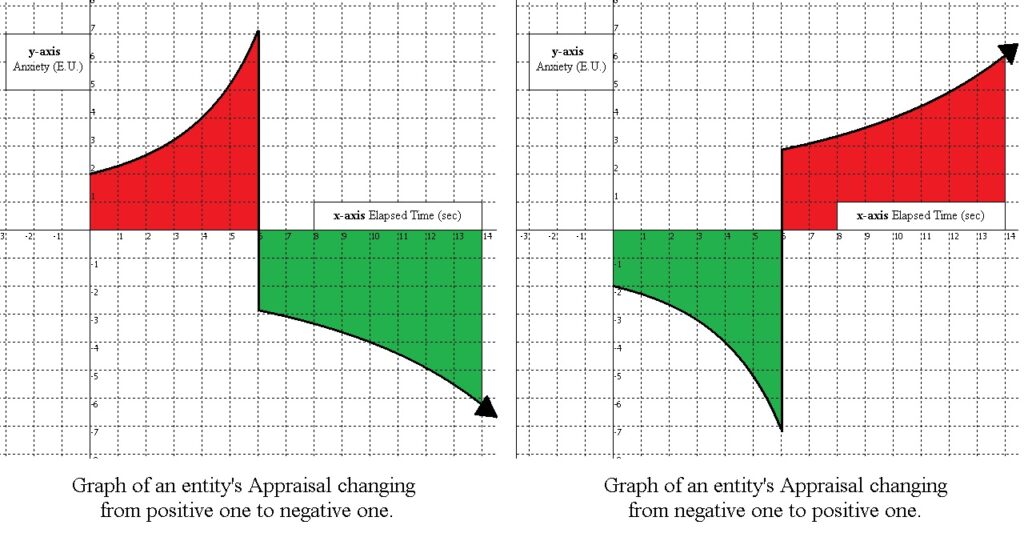

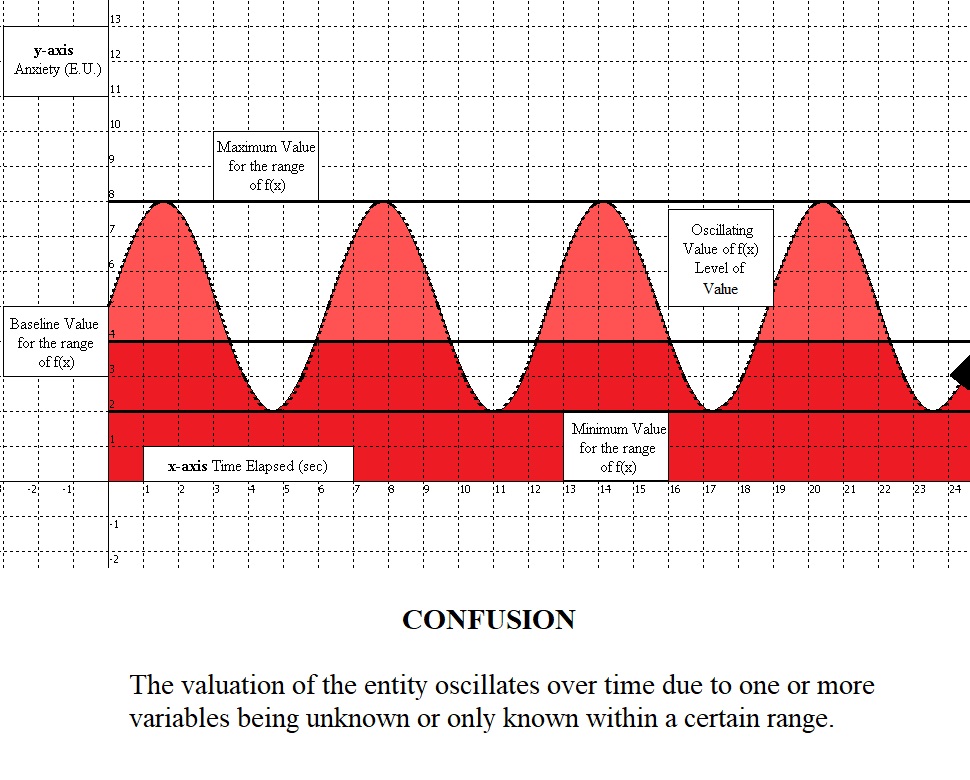

In each case, the 1:1:1:1 Ratio is still maintained, but becomes a 2:2:2:2 for all parties (for more on the 1:1:1:1 Ratio, see Article two, question number four in this series Reframing Anxiety as a Resource). The self, for example, imagines themself to be another person while vicariously experiencing the other’s situation, so the ratio is upheld.

It should not come as a surprise that the other pairs of Category II Emotions are also prevalent in popular cinema, books, or other works of art that seek to sway an audience one way or another, often times for artistic or rhetorical effect. In more benign cases, being able to readily identify when and how this is occurring can help give an audience a greater appreciation for the work and effort that went into crafting a message or story, or to critique the narrative if it fell short in some regard. In more malignant cases, it can afford audiences some inoculation against being manipulated via bias or prejudice by being better able to recognize it.

For the case of Sympathetic Shame, if the self were the passive party observing another and wanted a targeted other to succeed, but they failed, then the self would be modeled to feel Sympathy in Affect Engineering. Correspondingly, the targeted party, if they were aware that they were being empathized with, would feel Shame; shame, in this case, is more a sense of disappointment at having failed to achieve a goal that one desired to achieve coupled with the acknowledgment that others around expected or wanted the individual to achieve it. The self, in turn, would experience this sense of disappointment or Shame secondhand and vicariously in Affect Engineering’s framework, even if the self were the only one feeling Sympathy for the targeted party’s plight at having failed.

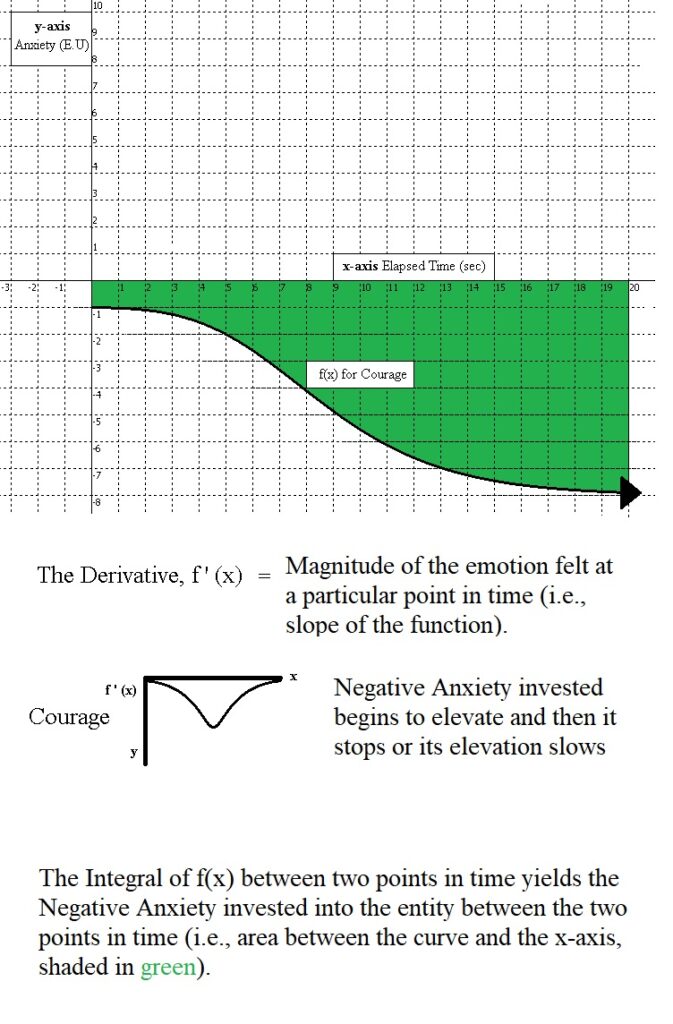

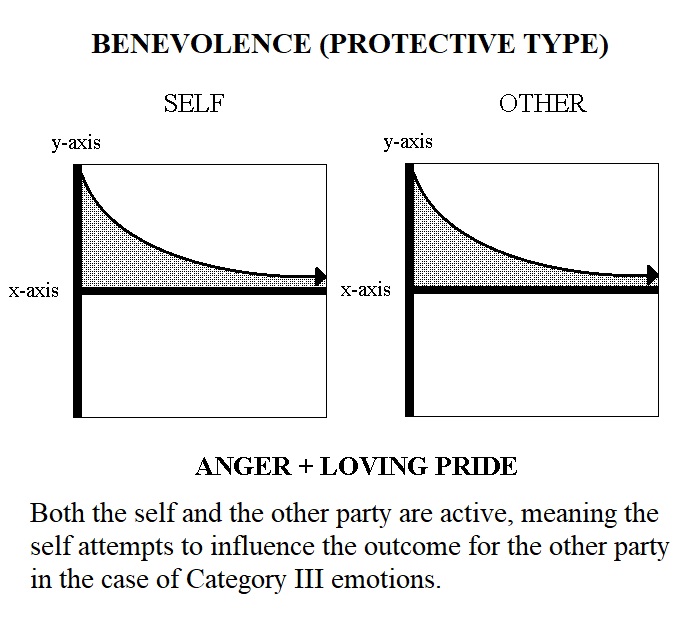

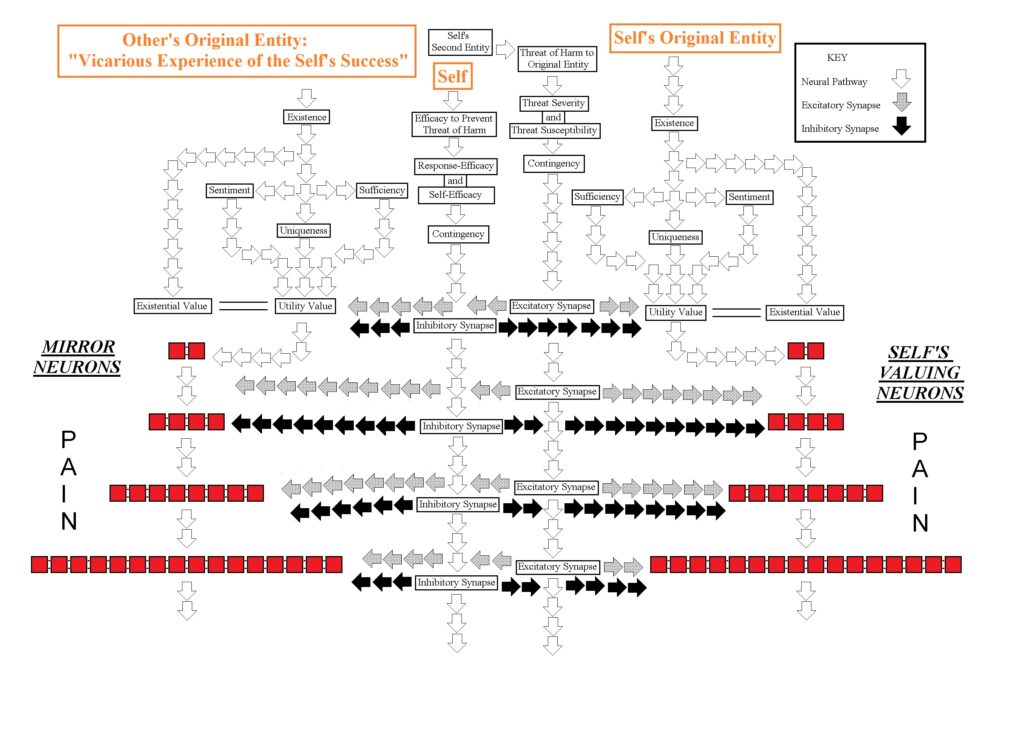

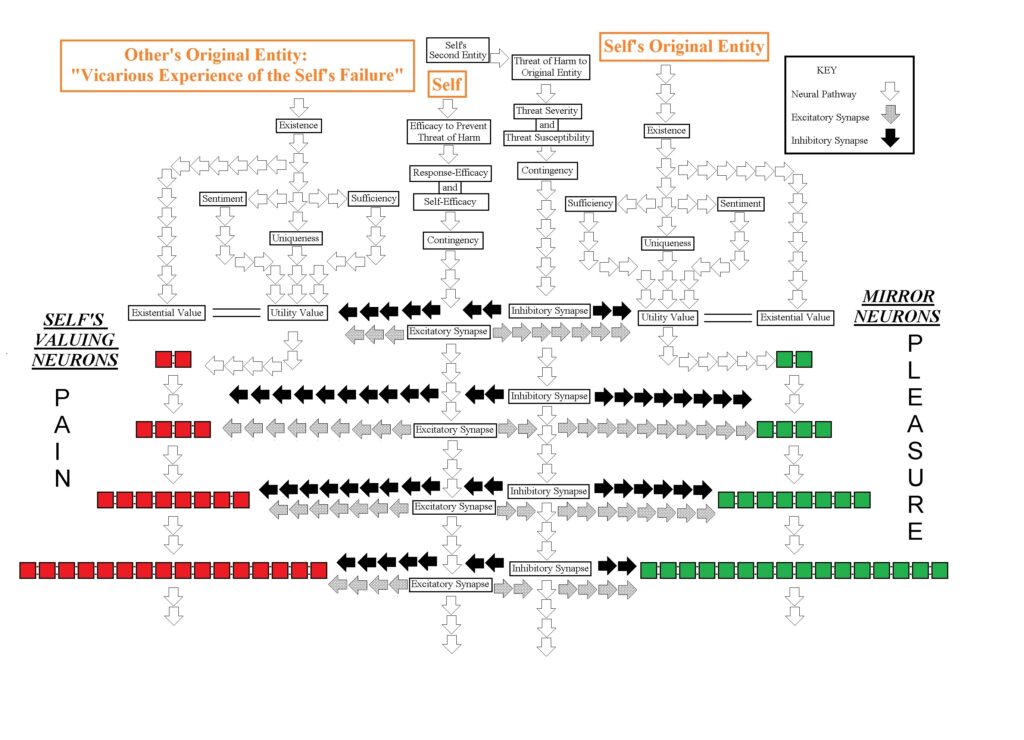

Image 4a (below) Sample neural model for Sympathetic Shame, where the self is the passive party and feels Sympathy and Vicarious Shame.

Image 4b (below) Sample neural model for Sympathetic Shame where the self is the active party and feels Shame and Vicarious Sympathy.

- In the Sympathy and Vicarious Shame variant of Sympathetic Shame, the self wants the targeted party (e.g., hero, protagonist, etc.) to achieve their goal, but the hero is unsuccessful in their endeavors. The character of Jack Dawson in James Cameron’s movie Titanic is a good example of this, as most audience members who watched the film wanted him to survive. This would be an instance of Sympathy in Affect Engineering (i.e., the self wants the target to succeed, but the they fail). In this particular case, the target of empathy, Jack, made it almost all the way to the finish line, but unfortunately fell short just before rescuers came and saved Rose. Jack’s fate, by many, is viewed as undeserved and unfair given all the other things he survived through to get there.

- The targeted party would be modeled to feel Shame at the acknowledgement that the self or anyone empathizing with their situation, wanted them to succeed, but they were unable to succeed, and this leads to disappointment in those witnessing it.

- The self would be modeled to feel vicarious Shame, imagining themself as the hero feeling Shame at having failed to achieve their objective and everyone else wanted them to, even if the self is the only one feeling sympathy for their failure.

- The hero or protagonist in this case, feels vicarious Sympathy, imagining themself as the self or another spectator wanting them to succeed but being compelled to witness their failure and become disappointed.

An example of Sympathetic Shame (e.g., Sympathy and Vicarious Shame variant) felt by the audience. Jack and Rose on the floating piece of wood from the movie Titanic (1997)

The above two Category II Emotions of Loving Pride and Sympathetic Shame are often used in narratives where an author, politician, content creator, artist, or marketer to name a few fields, wants to align the audience with a particular group or ideals, such as the protagonist, the hero, or whatever values they espouse.

In contrast, on the other side of the spectrum are Hate with Humiliation and Antipathy with Mercy. These Category II Emotions are generally reserved for targeted parties that the creator of a narrative desires to be viewed as antagonists, villains, or in politics, any person or group that one may seek to demonize or suggest that their values are less than wholesome.

If the self is passively observing a target party (e.g., a villain), wants the villain to fail at their objective, and the target party fails, then the self would be modeled to feel Hate in Affect Engineering, that is to say, delight at the failure of the other. Correspondingly, the target party or villain in this case, would feel Humiliation upon acknowledging that the self or other empathizing parties wanted them to fail at their objective and they did fail. The sense of humiliation here arises from the target being aware that observers disapprove of their objective and are celebrating upon their failure.

Meanwhile, the self, passively observing in this example, would experience the target’s sense of humiliation secondhand and vicariously.

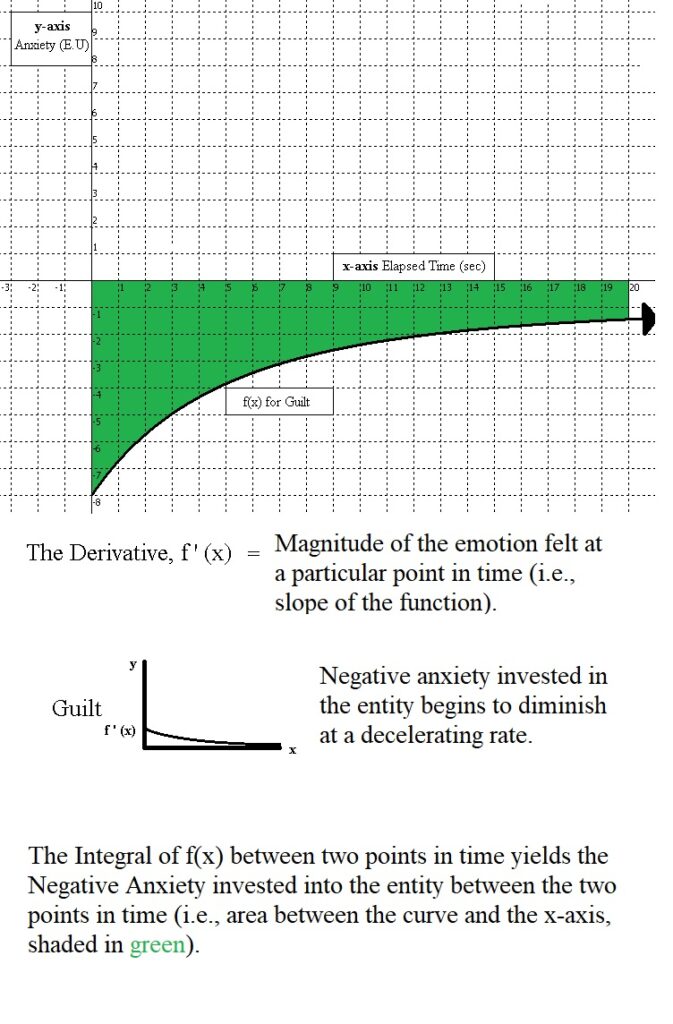

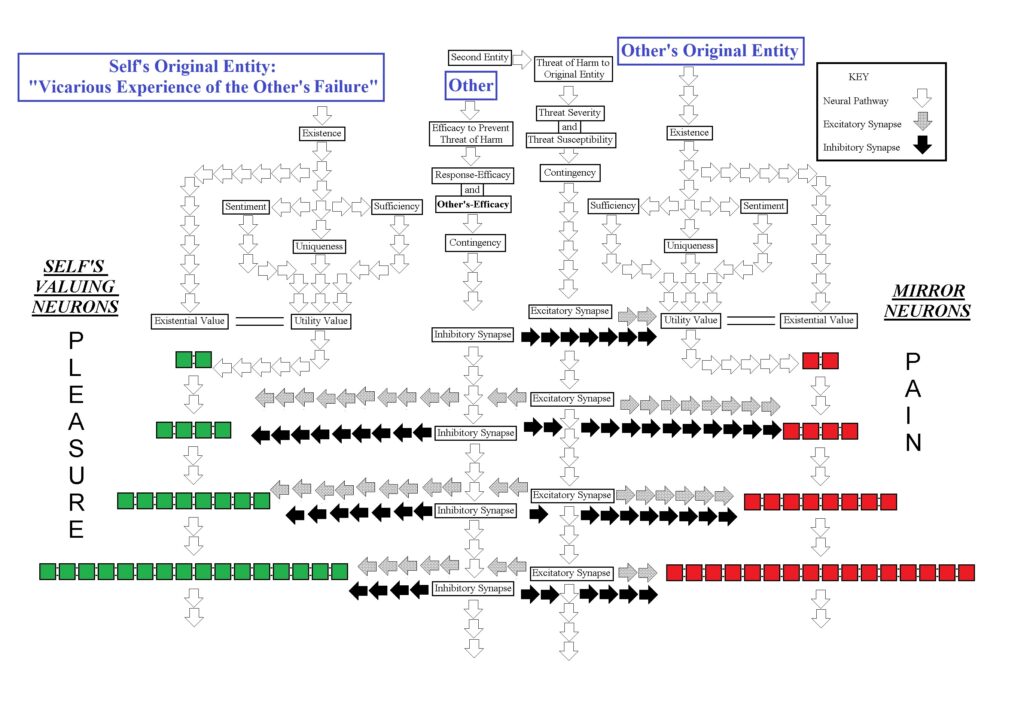

Image 5a (below) Sample neural model of Hateful Humiliation where the self is the passive party and feels Hate and Vicarious Humiliation.

Image 5b (below) Sample neural model of Hateful Humiliation where the self is the active party and feels Humiliation and Vicarious Hate.

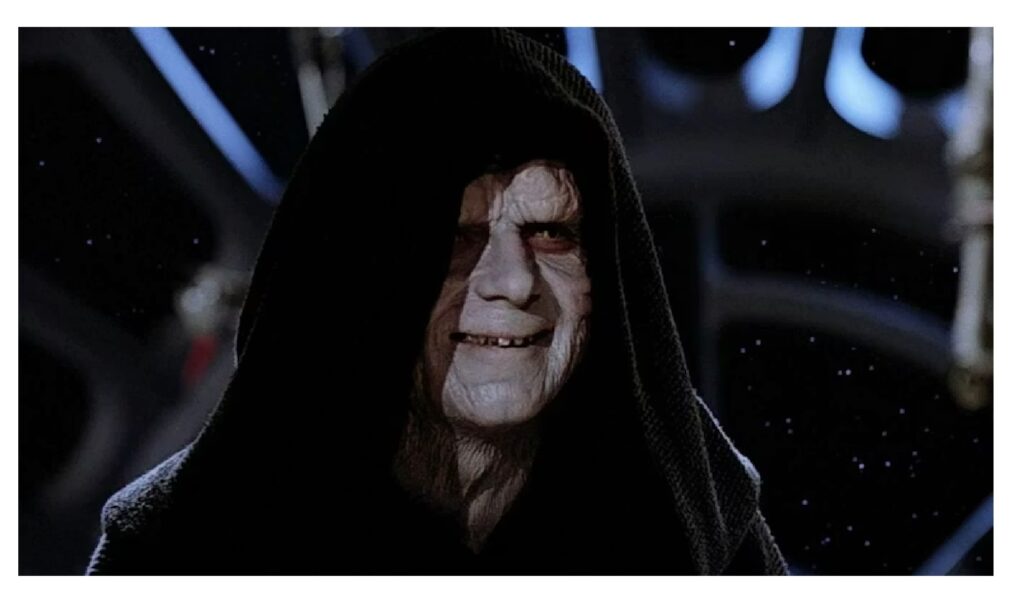

- In the Hate and Vicarious Humiliation variant of Hateful Humiliation, the spectator (e.g., the self) wants the villain (the target party) to fail by being unsuccessful and the villain was unsuccessful. This would be an instance of Hate, as the self wants the hero to fail and the villain does fail. In popular films, this would be exemplified by Emperor Palpatine from the Star Wars franchise, or Pennywise from the movie It. These are both characters that are relatively easy for audiences to cheer against and hope for their downfall, as neither one has any particularly redeeming qualities and they are easy to label, for lack of a better word, as evil.

- The villain (the target party) would be modeled to feel Humiliation at the acknowledgement that the self wanted them to fail and they were unable to achieve their aims.

- The self feels Vicarious Humiliation, imagining themself as the villain feeling Humiliation.

- The villain, in this case, would be modeled to feel vicarious Hate, imagining themself as the self or another spectator wanting them to be unsuccessful and celebrating their failure.

An example of Hateful Humiliation (e.g., Hate and Vicarious Humiliation variant) felt by the audience. Emperor Palpatine from the Star Wars franchise.

An example of Hateful Humiliation (e.g., Hate and Vicarious Humiliation variant) felt by the audience. Pennywise from the movie It.

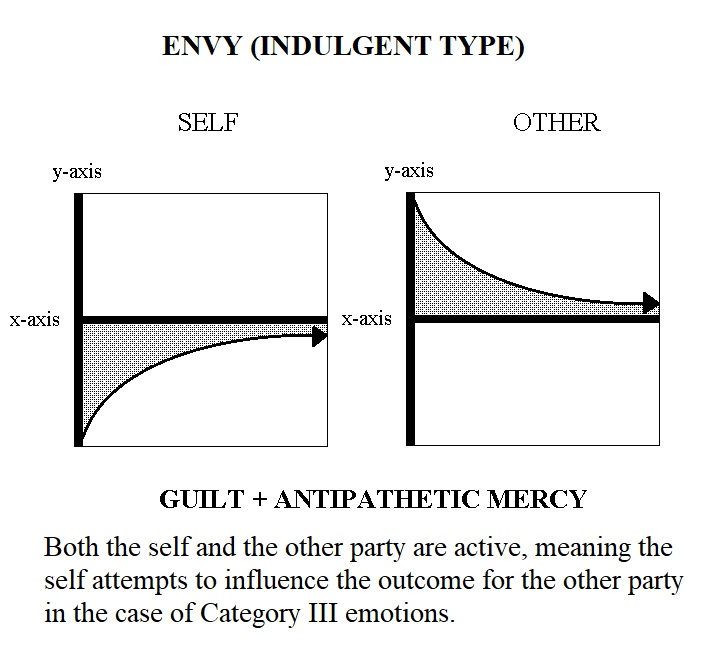

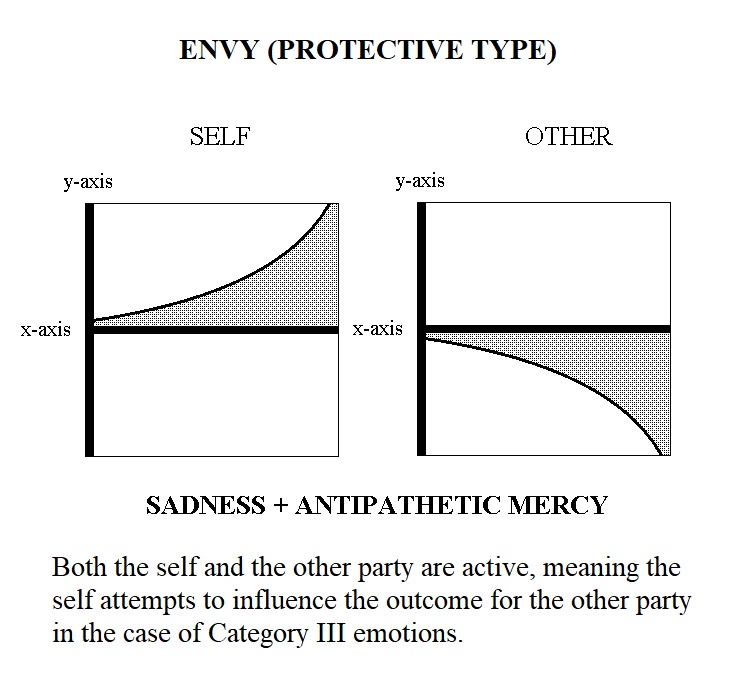

Fourth on this list is the situation where the self is a passive party observing a target party (e.g., a villain), wants the target party to be unsuccessful at their objective, but the target party succeeds. The self would be modeled to feel Antipathy in these instances, as the target party ends up successfully achieving their aims despite the self not desiring this to have occurred. Correspondingly, the target party would be modeled to feel Mercy (e.g., a sense that they have escaped justice, either obtaining an unearned reward or evading deserved punishment for their actions) in Affect Engineering at having succeeded despite the fact that those observing desired or expected for them to fail to achieve their objective (e.g., if their actions are in the wrong). Additionally, the self, passively observing, would experience the target’s sense of mercy secondhand and vicariously.

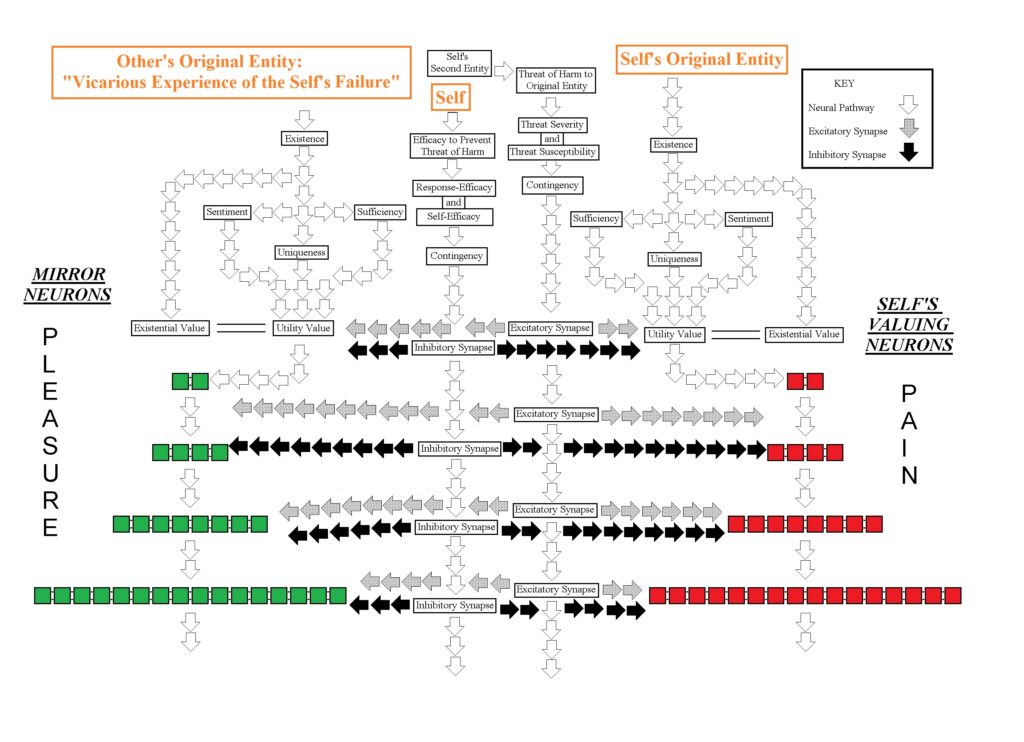

Image 6a (below) Sample neural model of Antipathetic Mercy, where the self is the passive party and feels Antipathy and Vicarious Mercy.

Image 6b (below) Sample neural model of Antipathetic Mercy where the self is the active party and feels Mercy and Vicarious Antipathy.

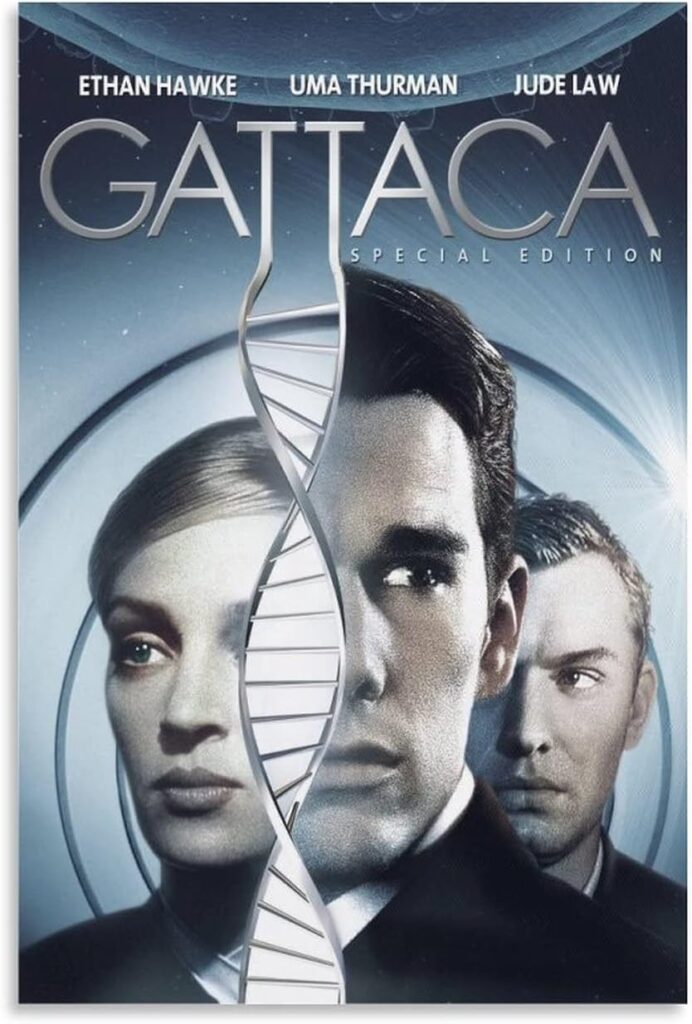

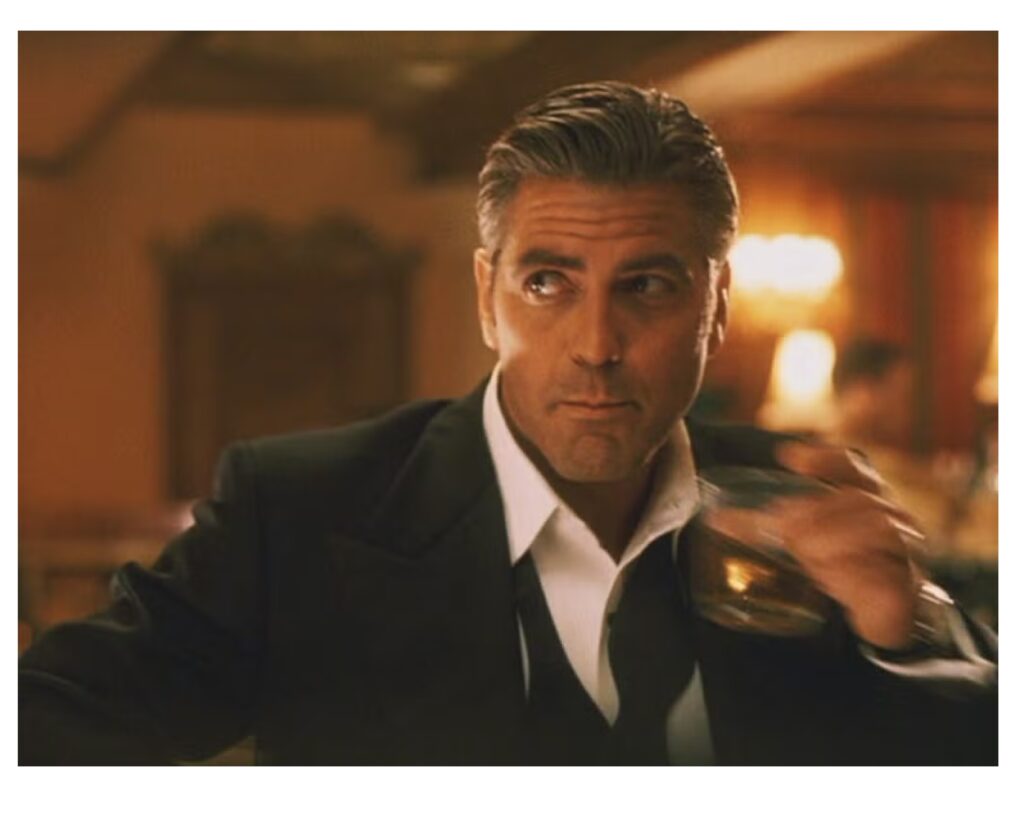

- In the Antipathy and Vicarious Mercy variant of Antipathetic Mercy, the spectator (e.g., the self) wants the villain or, antihero in some cases, to fail, but they are successful. This is modeled as an instance of Antipathy in Affect Engineering as the self wanted the target to fail, but they succeed anyway. The character of Joe Goldberg in the series You is an example of this, as the character in the series commits some fairly egregious deeds ranging from theft, to kidnapping and murder, yet manages to repeatedly escape justice, even if for no other reason than being the main character of the show and possessing plot armor, so to speak, along with the benefits that go with it (“You” trailer). Another example would be Danny Ocean in the 2001 remake of Ocean’s Eleven (e.g., Ocean’s Eleven trailer). These types of characters are also often written as being very charismatic, which can help enable them to earn a pass for their wrongdoings from observers and those empathizing with them.

- The targeted party (e.g., a villain or an antihero) would be modeled to feel Mercy at the acknowledgement that the self wanted or at least should expect them to fail, but they were successful nonetheless.

- The self would be modeled to feel Vicarious Mercy, imagining themself as the villain feeling Mercy, even if the self is the only one mercifying them.

- The villain, or alternatively an antihero, would be modeled to feel Vicarious Antipathy, imagining themself as the self or another spectator wanting them to be unsuccessful but being disappointed because they succeeded despite this.

An example of Antipathetic Mercy (e.g., Antipathy and Vicarious Mercy variant) felt by the audience. Joe Goldberg from the series You.

An example of Antipathetic Mercy (e.g., Antipathy and Vicarious Mercy variant) felt by the audience. Danny Ocean from the 2001 remake of Ocean’s Eleven.

Lastly, Neutrality with Vicarious Loneliness or Vicarious Neutrality with Loneliness would be modeled to arise if the passive party neither desires for the active party to succeed nor fail (e.g., both are weighted the same). This, in essence, would be the absence of an empathetic response in Affect Engineering, or an instance of Indifference. The outcome of the scenario for the active party has no effect on the state of the passive party; there is no correlation one way or the other.

2) Why are there only four degrees of empathy in Affect Engineering if there are five pairs of Category II Emotions?

SHORT ANSWER

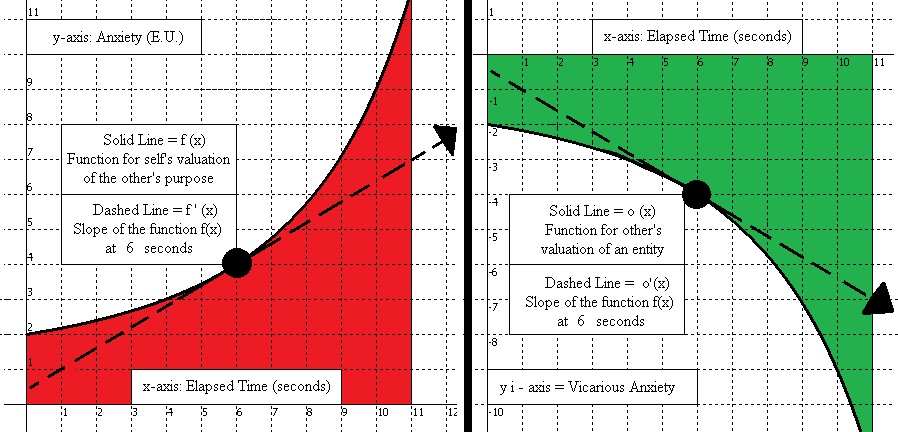

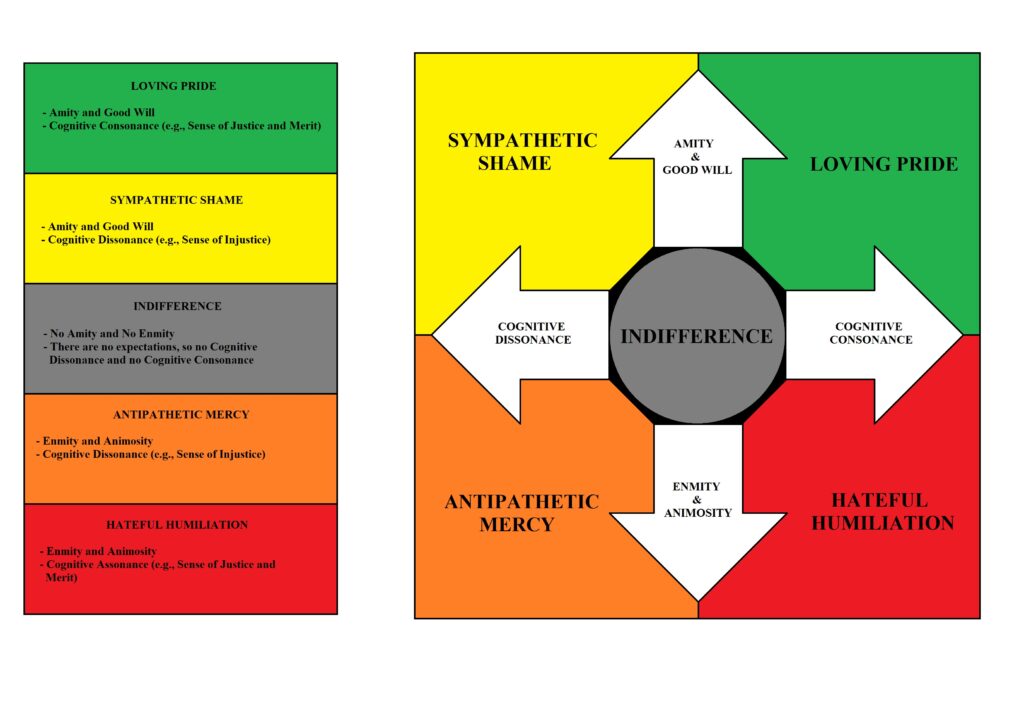

The conception of empathy in Affect Engineering can be likened to a compass with four directions represented by its four degrees. These four degrees can be mapped out on a pundit square with one scale being a measure for amity and goodwill against enmity and animosity, while the other scale is a measure for the amount of cognitive dissonance vs. cognitive consonance present, and the difference between expectations versus reality. The absence of amity and enmity along with the absence of cognitive dissonance and consonance would comprise the fifth pairing, Indifference, a general lack of empathy.

IN DEPTH EXPLANATION

Compass Mapping of the Four Degrees of Empathy

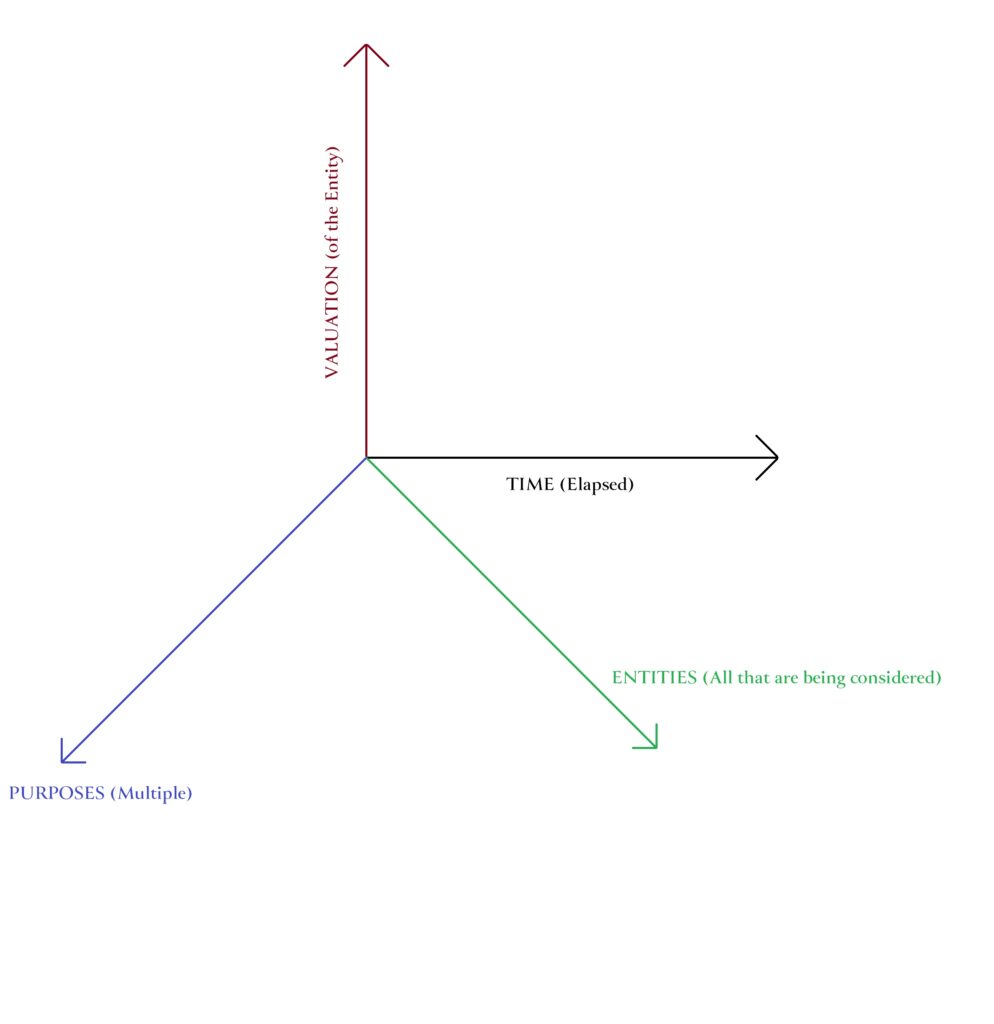

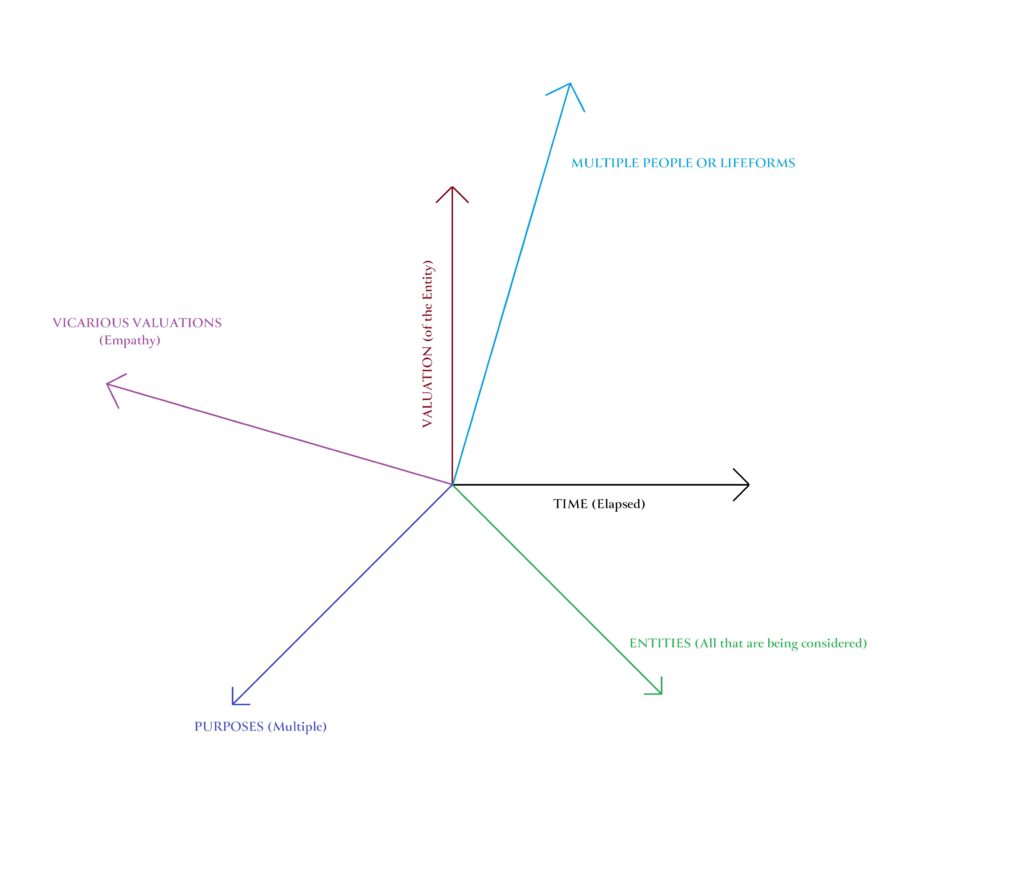

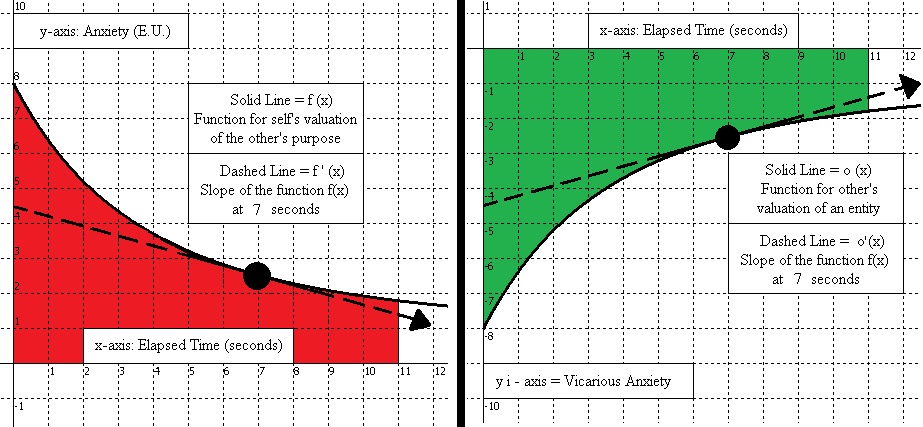

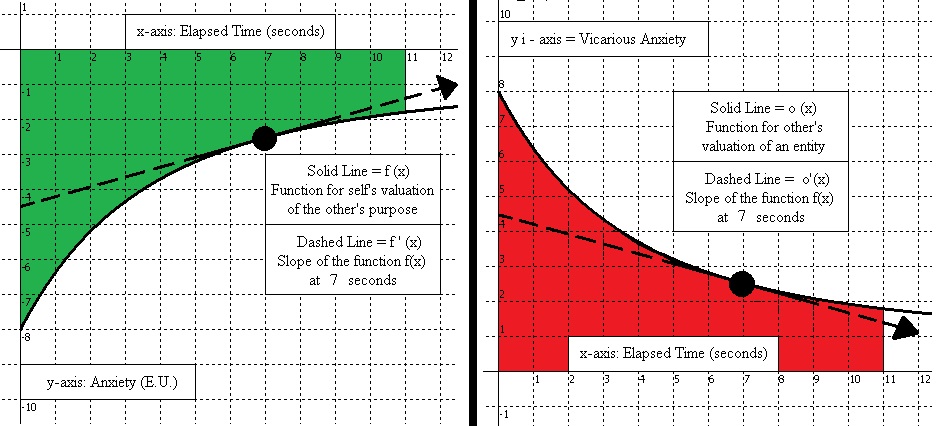

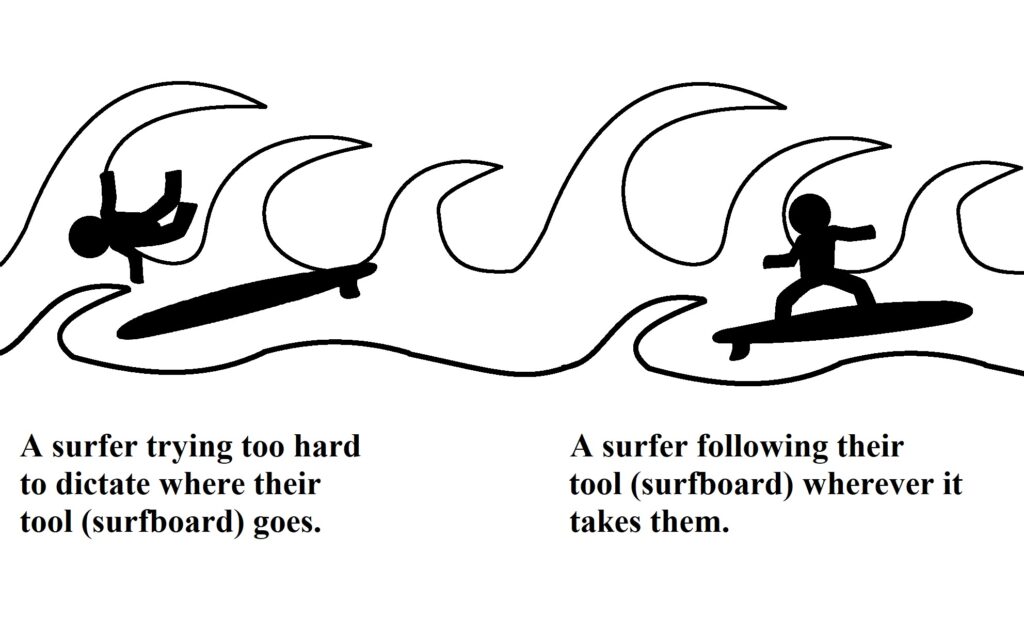

Assuming that the empathizing party is the passive party, then there are two questions that Category II Emotions address:

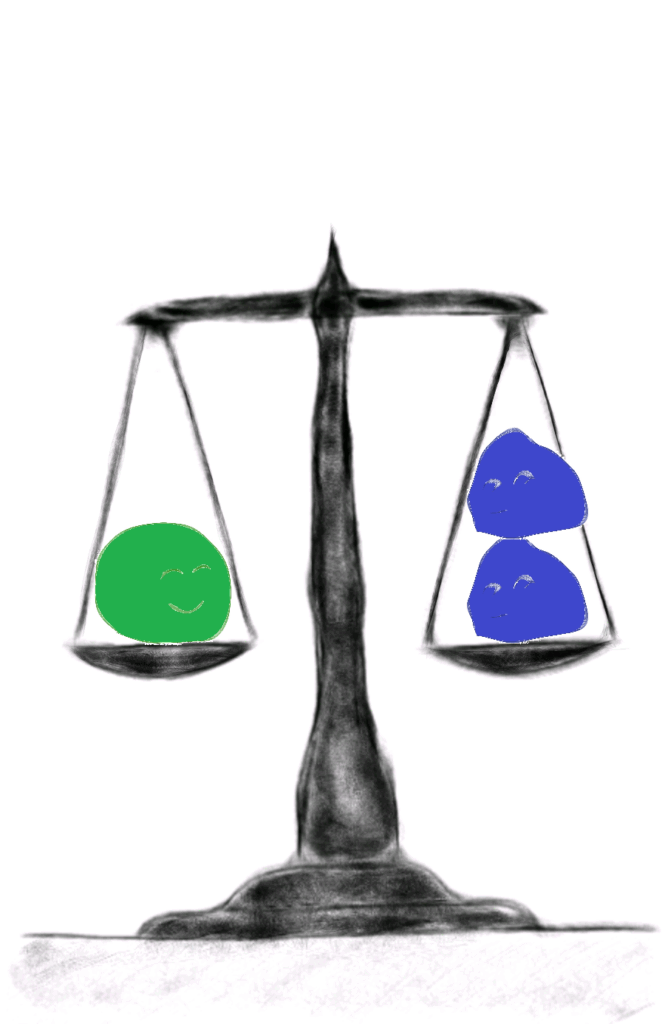

- Does the empathizing party want to vicariously experience the targeted party (i.e., the other) succeed or fail at their objective?

- Does the targeted party (i.e., the other) succeed or fail?

For instance, if the self is passively observing another party attempt to achieve an objective, a two by two pundit square results with the four possibilities.

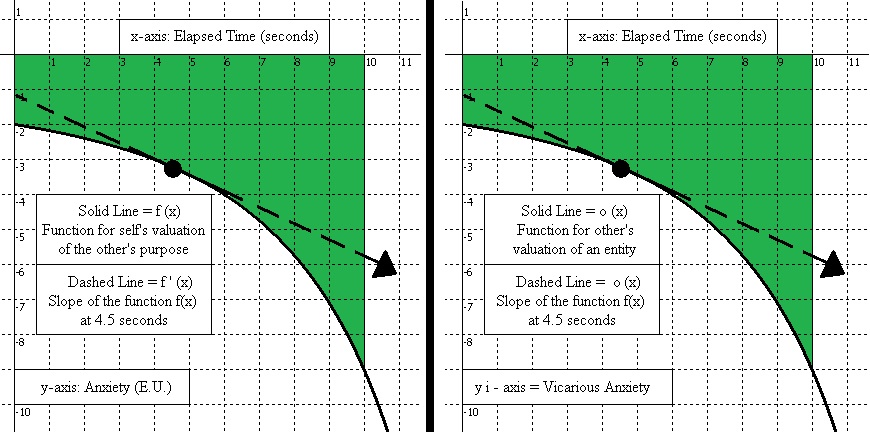

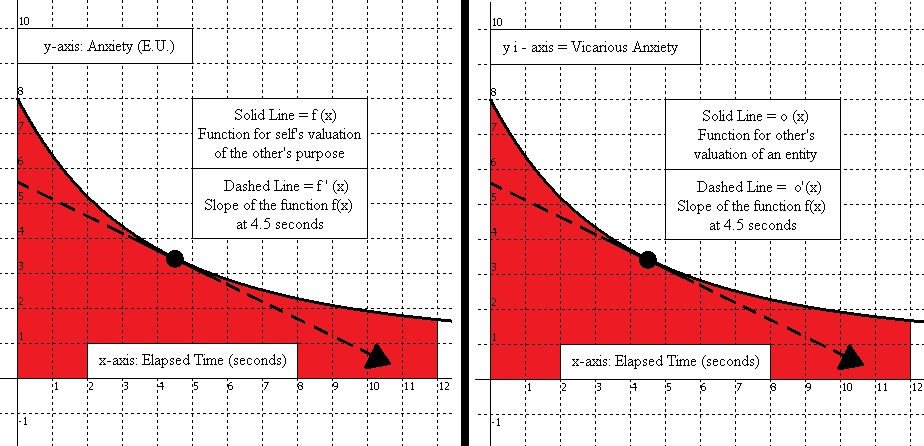

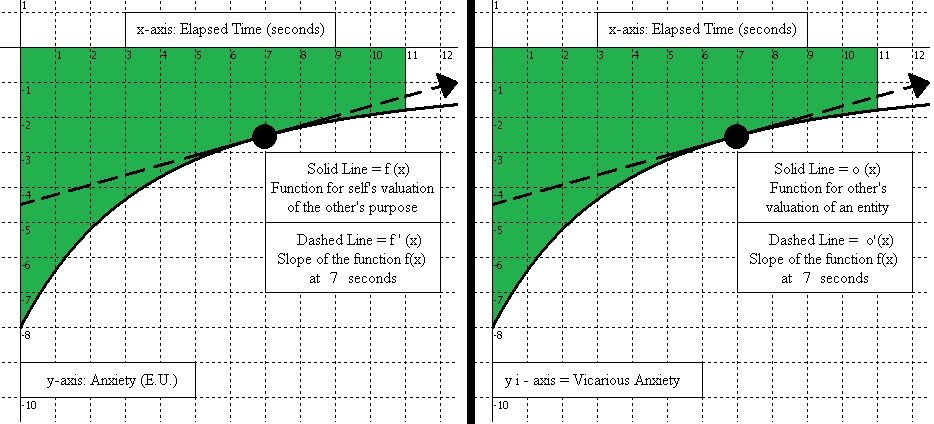

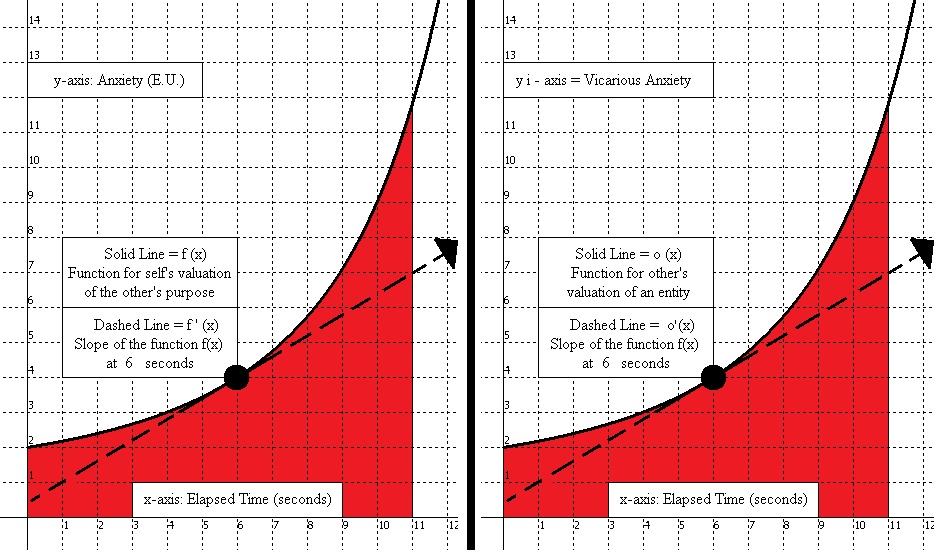

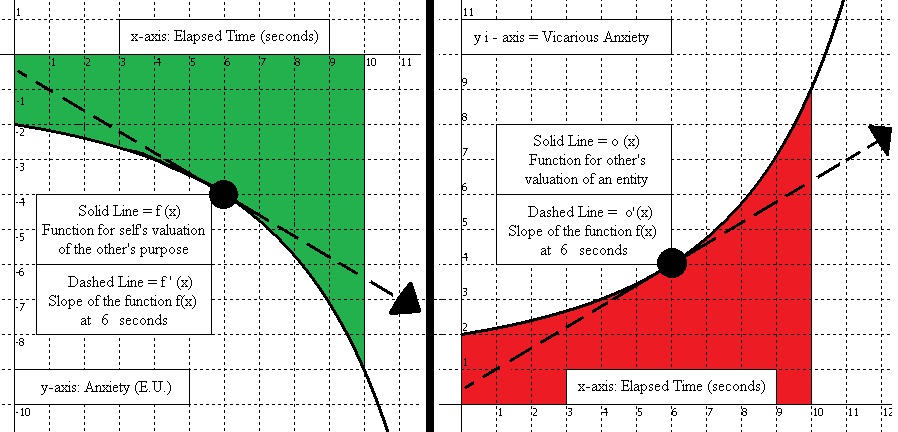

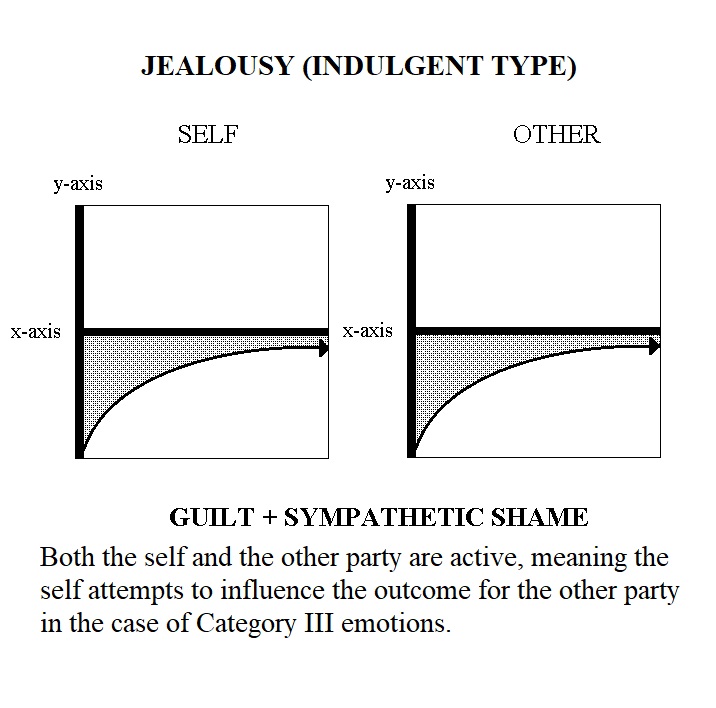

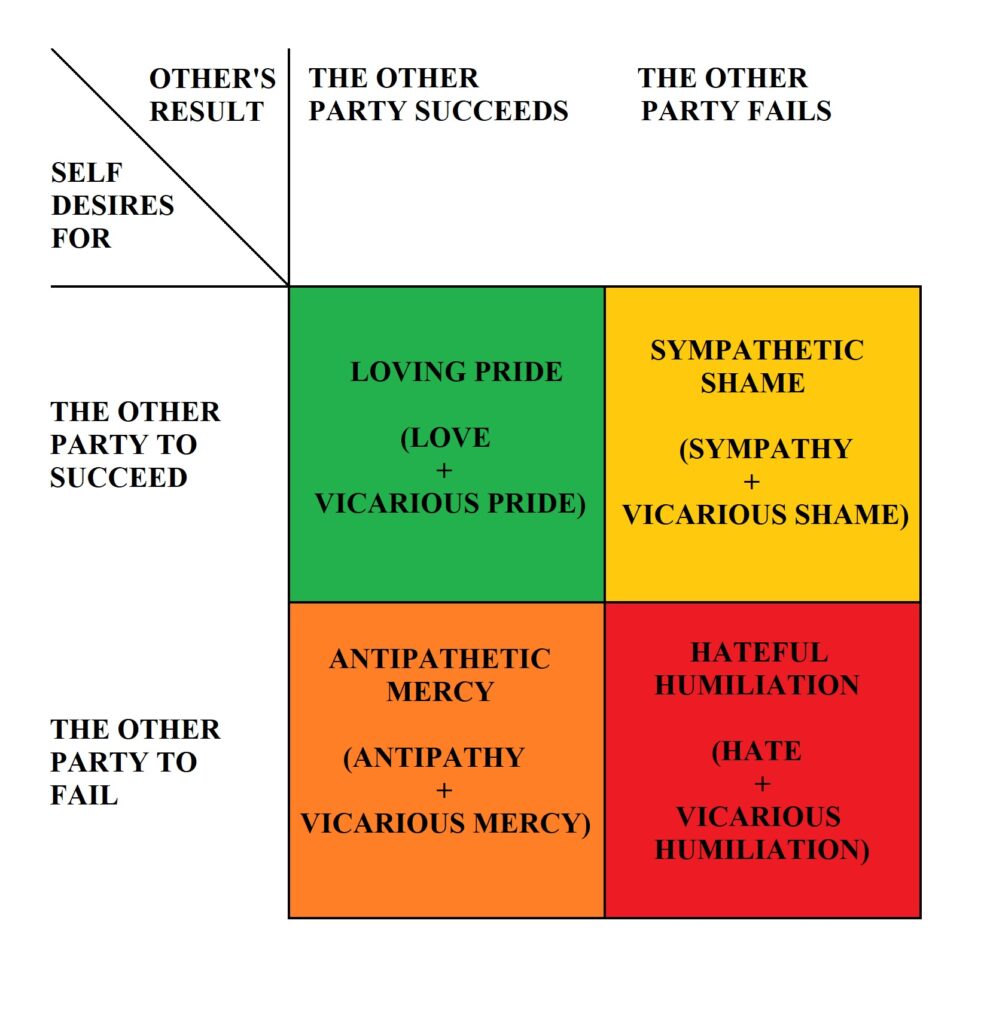

Image 7 (below) What the self feels when the self is the passive party and the other party is active.

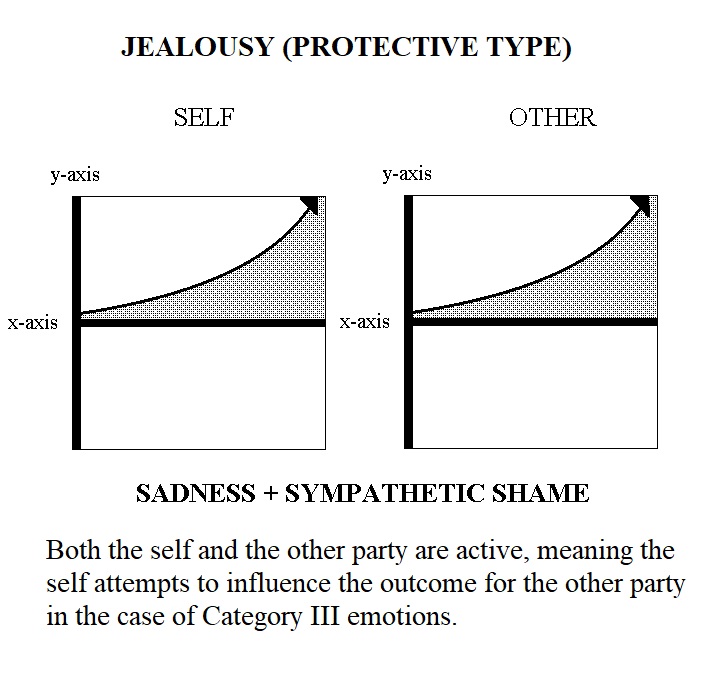

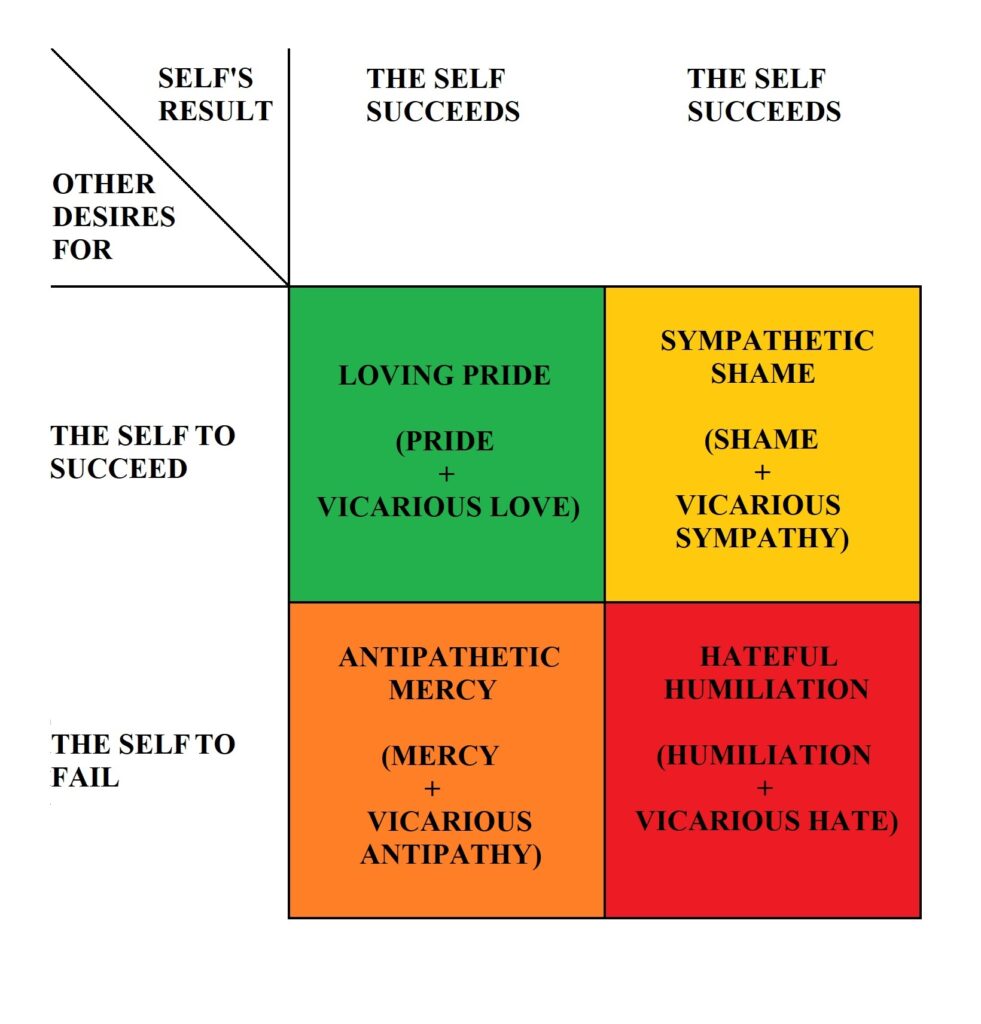

For instances where the self is actively working towards an objective and the other party is passively observing them, the pundit square is similar but the vicariously experienced emotions flip.

Image 8 (below) What the self feels when the self is the active party and the other party is passive.

The fifth, or perhaps better labeled zeroth degree of empathy, would occur when the empathizing party does not lean one way or the other in regards to which outcome they prefer for the other party and there is neither cognitive dissonance nor consonance due to there being no expectations. This would be for Indifference (e.g., Neutrality and Vicarious Loneliness or Vicarious Neutrality and Loneliness).

3) Why does Affect Engineering bother to distinguish emotions that are experienced vicariously depending on whether or not one party has the ability to influence the outcome of another party’s situation?

SHORT ANSWER

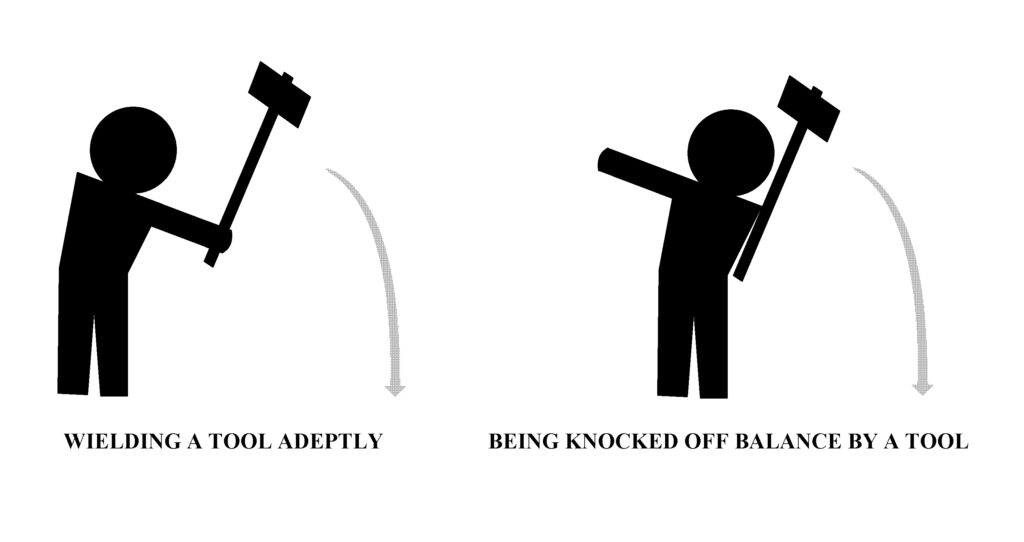

An individual who is vicariously and passively experiencing another party’s success or failure will necessarily experience it differently than they would if they were actively trying to shape the outcome of the other party’s situation with their actions.

IN DEPTH EXPLANATION

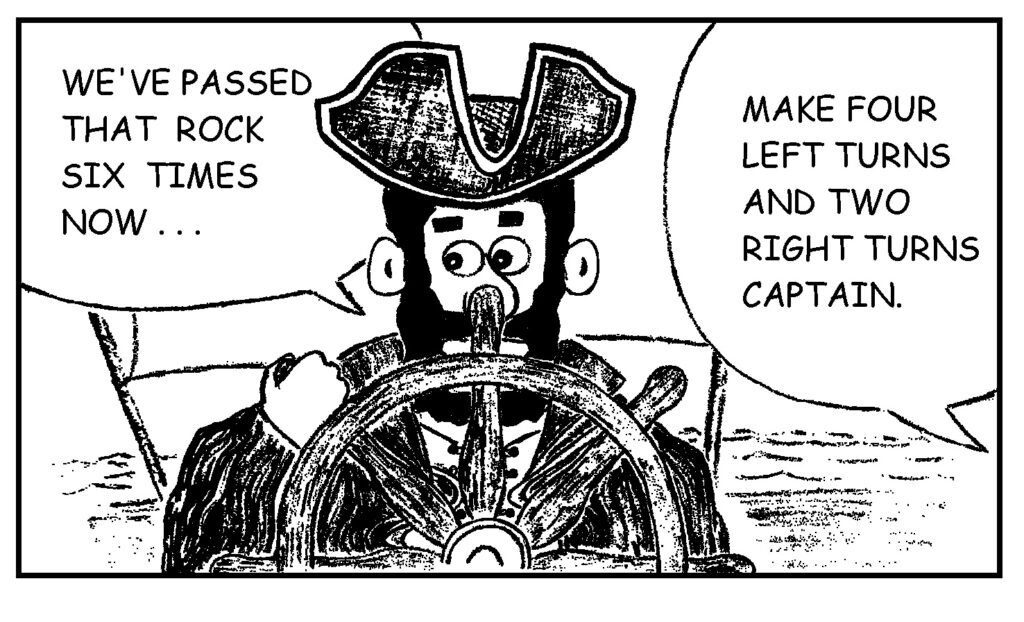

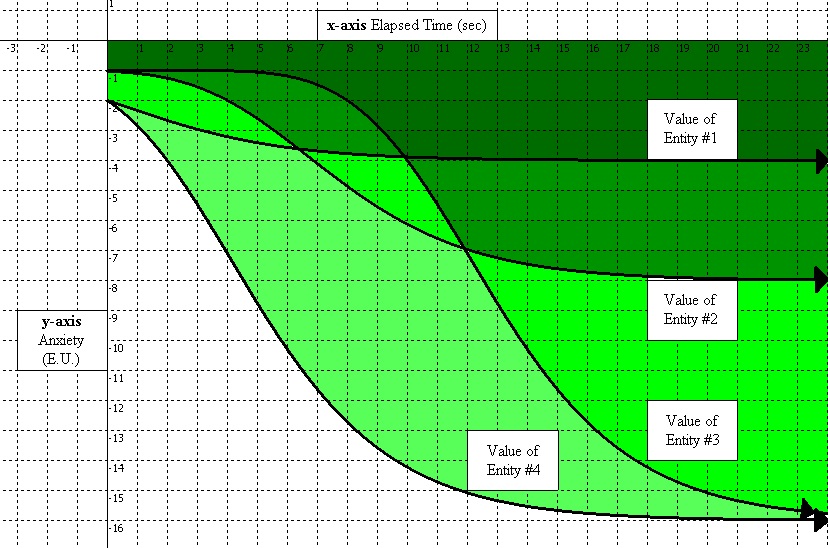

The distinction between Category II Emotions (Interpersonal Emotions) and Category III Emotions (Compound Interactive Emotions) lies solely within the answer to the question, “Does the empathizing party possess the ability to influence the outcome for the targeted party they are empathizing with?” This distinction is somewhat similar to the difference between fans of a sports team watching them on television and cheering them on from home or at a bar in isolation from the event, as opposed to cheering them on at the stadium or arena they are competing in.

Watching from home or at a bar effectively distances the fan far enough away from the event that they can only observe and vicariously experience the team’s situation from afar. There is nothing that they can do that might reasonably influence the outcome of the game.

However, a fan cheering their team on from a stadium can shout and cheer for their chosen team to boost morale; alternatively, they can boo, jeer, and heckle athletes and competitors from the opposing team during crucial moments to try and disrupt their concentration. While they can not play the sport themselves in lieu of the professional athletes on the team, it does afford them some sense of influence over the atmosphere at the venue. Moreover, their emotions would more aptly be categorized as a Category III Emotion in these cases.

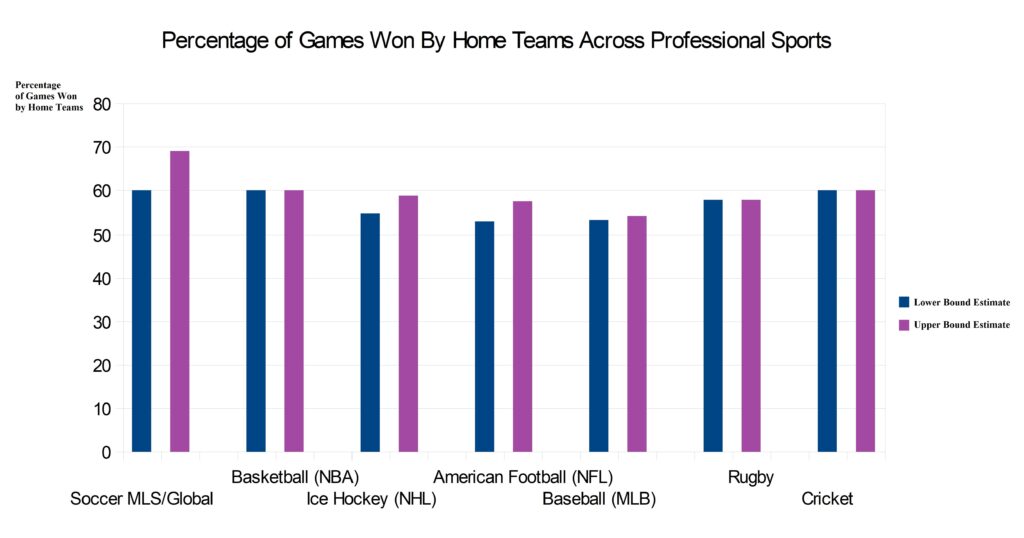

Although this is a relatively tame example of a Category III Emotion, it is a suitable enough example to highlight the difference between the two categories in Affect Engineering’s framework. For instance, having home field advantaged is well acknowledged in most professional team sports. Across the major professional sports league, during the course of a regular season, the home team generally wins more games on average than the away team:

Image 9 (below) Percentage of games won by home teams across major sports leagues. Source: Google Search Engine Result for lower and upper bound estimates.

Across these professional sports, home teams win more games on average than away teams (Soccer ~60-69%, NBA ~60%, NHL ~55-59%, NFL ~53-57%, MLB ~53-54%, Rugby ~58%, Cricket ~60%). Other factors such as familiarity with the venue, having less jetlag from not traveling, and being acclimated to an environment (e.g., high altitude, snow, or heat in certain regions), also play a large part in home field advantage.

What is life, however, without exceptions?

Anomalies

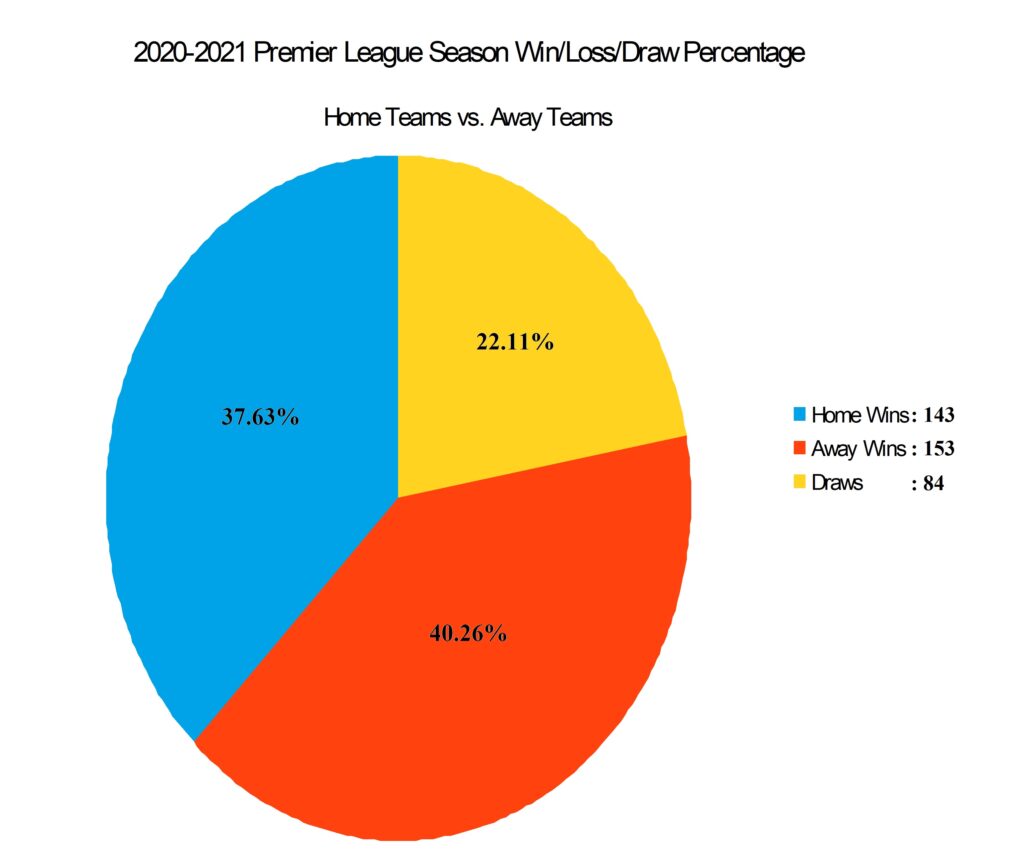

One exception to this home field advantage trend stands out among others. In its thirty three years and seasons of existence, the 2020-2021 season of the Premier League (soccer) is the only season that saw away teams win more games than home teams. This was also a season during which no fans were permitted in stadiums due to COVID-19 restrictions. It saw away teams win 40.3% of games against home teams, who won 37.9% of games.

Image 10 (below) – Away Teams 153 Wins – Draws 83 – Home Wins 144

Homefield advantage returned in the Premier League the next year and has remained for every subsequent year thereafter with home teams winning more games than away teams, as can be observed in the article “Crumbling fortresses – why are teams struggling to win at home?”.

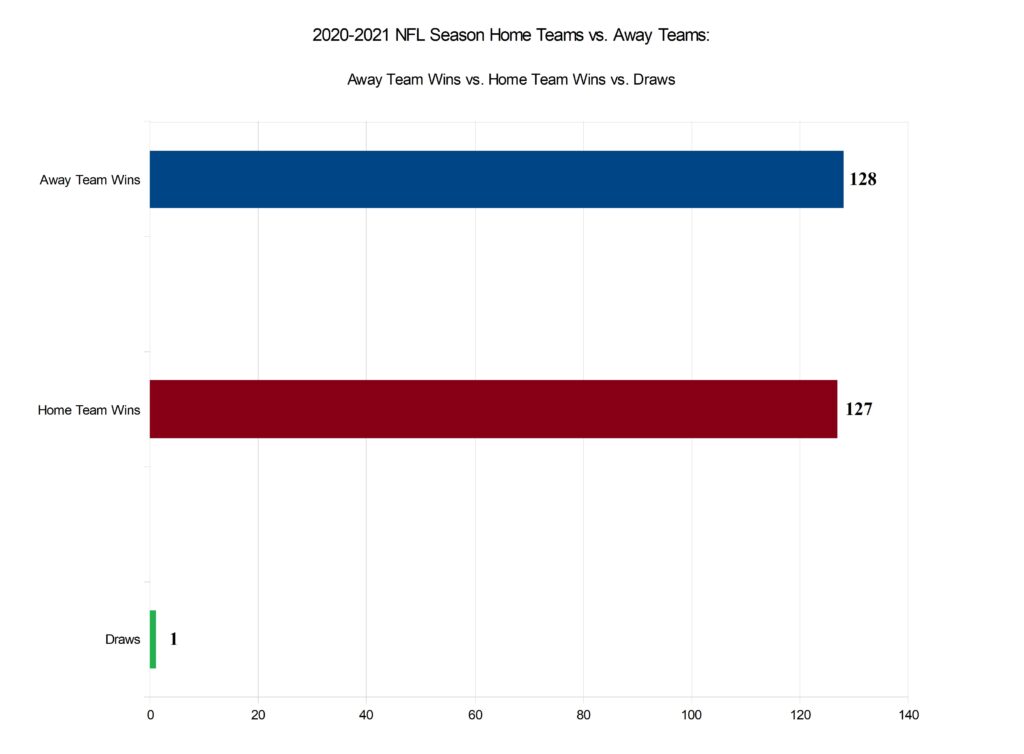

Also of note, the 2020-2021 NFL season was the only NFL season in its fifty plus year history, and only season since then, where home teams won fewer games than away teams (“What Happened to NFL Home-Field Advantage?”).

Image 14 (above) Home Team Wins = 127; Away Team Wins = 128, Draws = 1

Away teams were still traveling to less familiar venues, were jetlagged, and less acclimated to their environments, but with no homefield fans to create an atmosphere conducive to the home team winning, homefield advantage all but diminished for that year. During this season, the home teams odds of winning again away teams was reduced closer to chance or lower level than it was before or since then. This homefield advantage, as subtle and intangible as it is, virtually disappeared with the absence of fans in the stadium for a season, and then returned the following year and for every subsequent season thereafter in both leagues.

The implications of anomalies like this for modeling empathy in Affect Engineering are bit more straightforward fortunately. Judging by these two anomalies (the loss of homefield advantage that occurred during the absence of fans for these two leagues during the COVID lockdown), an observer might surmise the following: in general, fans who attend sporting events to cheer on their team or boo and jeer against rival teams are probably more inclined to believe that they contribute to their home team’s success more so than they would have if they had merely watched the game from home or at a bar where they could only passively watch it.

What this entails for Affect Engineering is that in the case of the sports fan, it would be more appropriate to model the empathy of fans who attend sporting events to cheer on their team and boo the opponent as a Category III Emotion, Compound Interactive Emotions, because they have the ability to influence, small as it may be on an individual level, the collective atmosphere at the venue where the event is taking place, and in some ways, the outcome. Category III Emotions will be examined in more detail in the next article of this series.

For the sports fan who watches and empathizes with their favorite sports team in isolation at home or with a small group of friends in a bar, it would be more appropriate to model their empathy as a Category II Emotion, or Interpersonal Emotion, as they have no tangible or easily identifiable means to influence the outcome of the event.

4) For what reasons might an individual intentionally alter their identification level with a target?

SHORT ANSWER

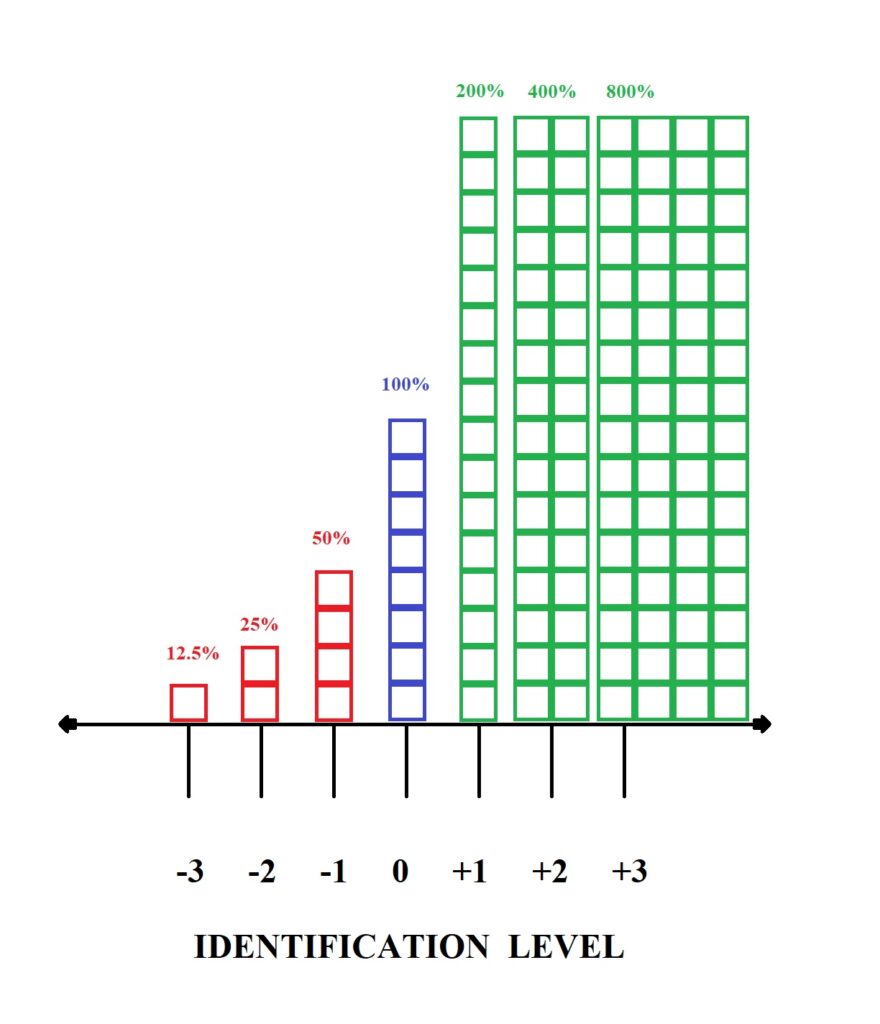

An individual might alter their identification level with a target by lowering it to avoid relating to someone or something potentially upsetting. Alternatively, they might intentionally elevate their identification level with a target by raising it abnormally to a heightened level if normal communication methods are inadequate for a situation.

IN DEPTH EXPLANATION

Identifying with extreme classes or types of people (e.g., serial killers, murders, criminals, heroes, celebrities, etc.) presents some unique opportunities and challenges to an individual. For an individual to identify with another person or lifeform, this entails putting themself in a different perspective to see the world from their point of view. Sometimes this might compel the empathizing party to confront their own capacity, or lack thereof, to commit certain offenses or perform certain heroic deeds under duress if they were in a similar situation. In the case of this last statement, two reasons for distancing oneself from a target (by not identifying with them or drastically lowering identification level) present themselves:

- Observers might choose to distance themselves from a serial killer or murderer (e.g., by dehumanizing or labeling them a monster) to avoid confronting the possibility that they too, might be capable of committing horrible crimes if they were in the same position.

- Similarly, observers might choose to distance themselves from a hero (e.g., by idolizing, them a saint, otherworldly, or putting them on a pedestal) to avoid confronting the possibility that may not be capable of performing a similar action if called upon to do so in a time of peril.

In other situations, identifying too much with a target can also make certain endeavors more difficult, such as warfare. Being called upon to fire at and potentially kill an enemy combatant, particularly one that the soldier personally knows nothing about and harbors no ill will towards, save that they are a citizen of another country that was also drafted into the same war but on the opposing side, requires a certain level of detachment that can be difficult to achieve under normal circumstances. These are instances where identification would be likely viewed as a general hindrance on one side (e.g., by warhawks), and viewed as a general necessity on the other side (e.g., by pacifists).

On the other side of this question, an abnormally heightened identification level with a target can prove useful, such as in a first encounter between different cultures, situations where there are unknowns and direct communication is not possible, or for identifying ideals towards which one wishes to aspire.

For the vast majority of situations though, an individual would most likely be inclined to identify with a target at an elevated level (e.g., at a higher level than they would if they were in the position) if it is necessary for the target’s well being, and normal communication is not possible. For example, a protective parent of a small baby, a pet owner, a horticulturist in a garden, or an owner of a vintage car (e.g., inanimate object) might identify with the target at a higher level than they would if they themself were in that position, perhaps in order to preemptively address issues related to their wellbeing that cannot be stated directly. Under ideal conditions, this state of hypervigilant or excessive identification would serve the purpose of helping the individual anticipate the targeted party’s needs and respond to them. Under less ideal conditions, this state of elevated identification might lead to infatuation or obsession, such as the idolization of a celebrity, and so moderation would be warranted.

Preview

The next article will examine Category III Emotions, the Compound Interactive Emotions, in more depth.

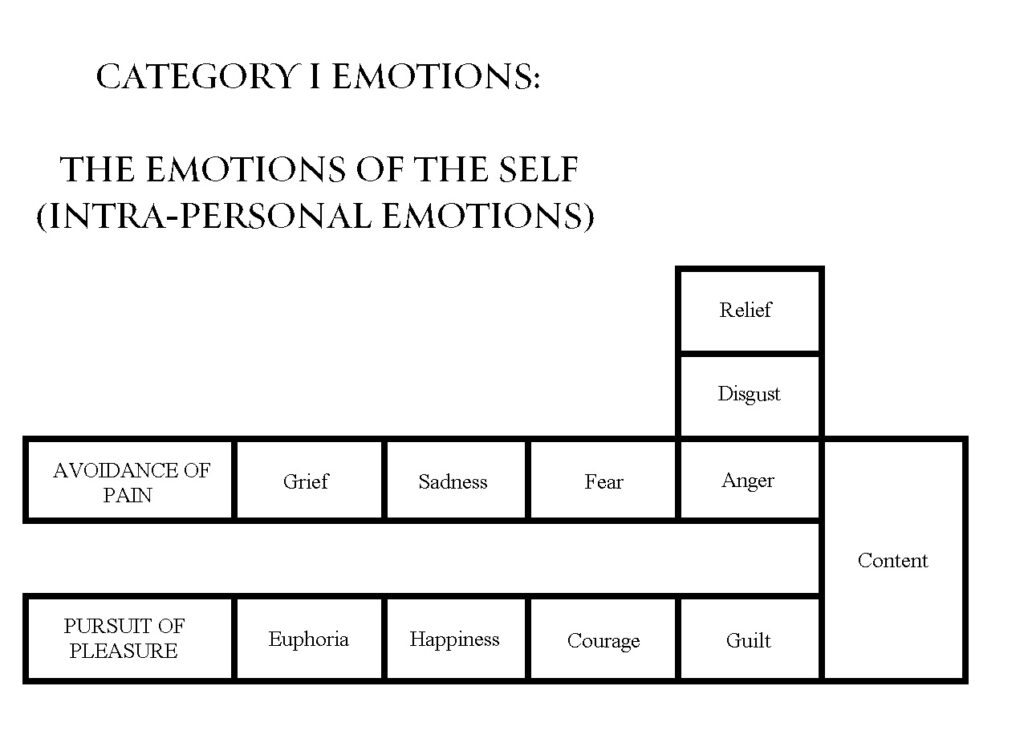

Previous: Article 7 of 12: Category I Emotions, the Intra-Personal Emotions or Emotions of the Self

Next: Article 9 of 12: Category III Emotions, the Compound Interactive Emotions